I thought I would revive these for the 75th anniversary of D-Day

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

I see some of the pictures have issues.

I'll fix those at a later date...

I hope you enjoy the tour

Day 4 - British & Canadian Beaches plus other sites

Creully - Chateau de Creullet - Montgomery's 21st Army Group Headquarters

Creully - 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial - DD Tanks & Chateau de Creully BBC HQ

Reviers - Neolithic Barrow Fort

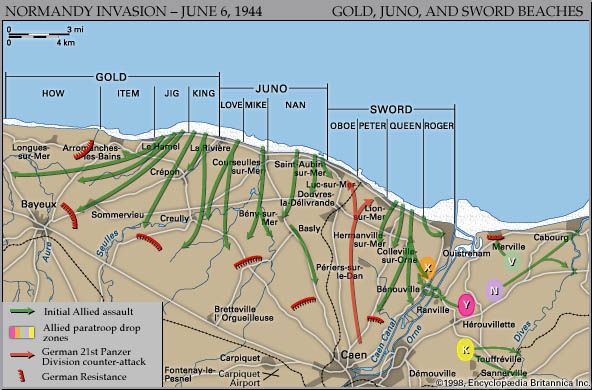

Beny-sur-Mer - Canadian Military Cemetery Periers Ridge - Overlooking Sword Beach - route of 21st Panzer Division counter-attack on D-Day

Periers Ridge - Royal Norfolk Regiment Monument - Belvoir Farm

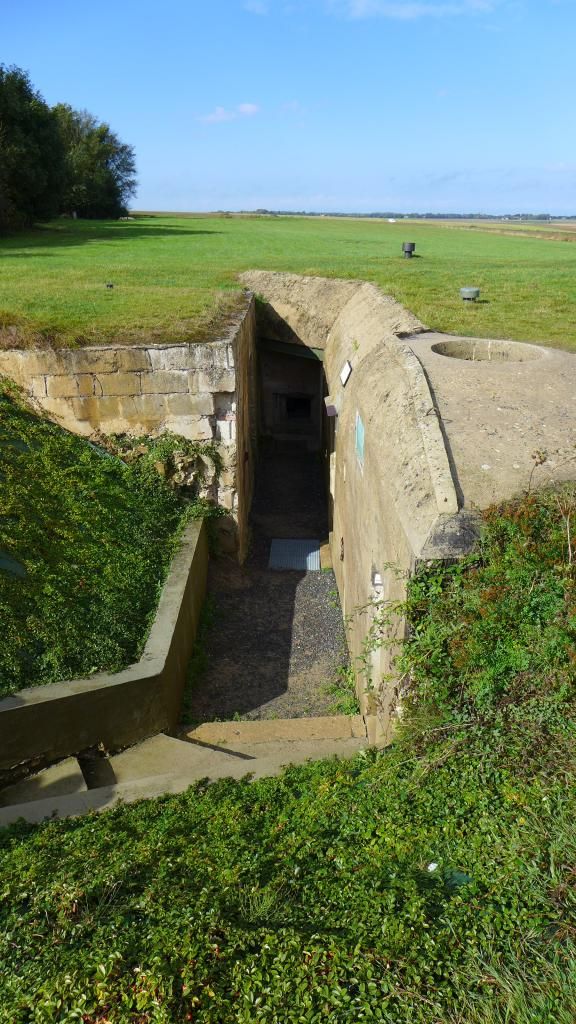

'Hillman' Strongpoint - Colonel Ludwig Krug's HQ taken by 1 Suffolks

Lunch - Hermanville-sur-Mer

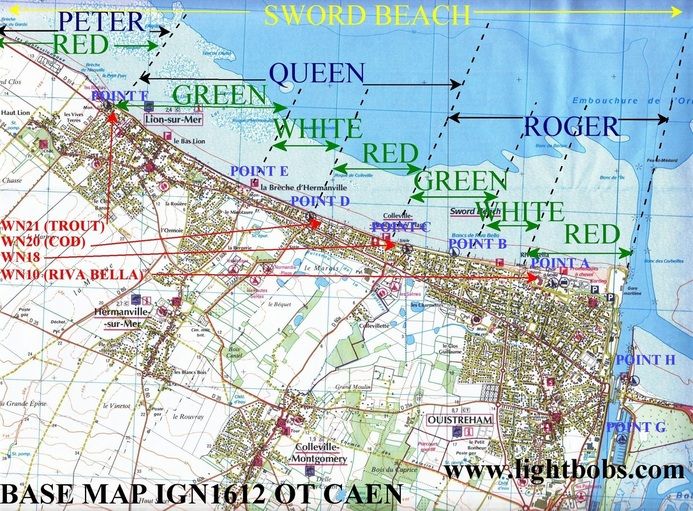

Sword Beach - Queen White - Hermanville - Assault area of British 3rd Infantry Division & Memorials

Sword Beach - Lion-sur-Mer - AVRE Tank (Petard Mortar) & Memorials for 41 Commando and Roosevelt

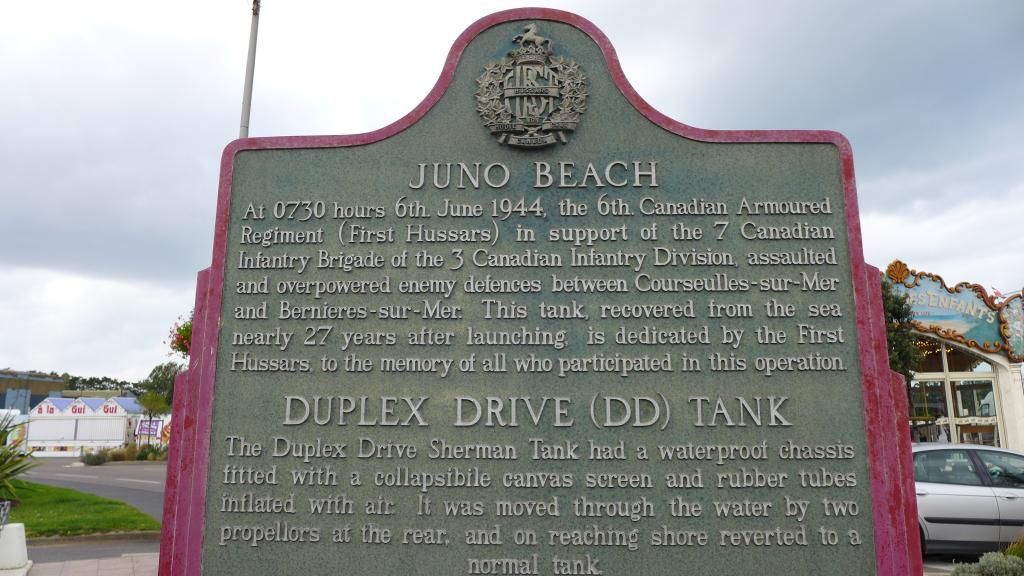

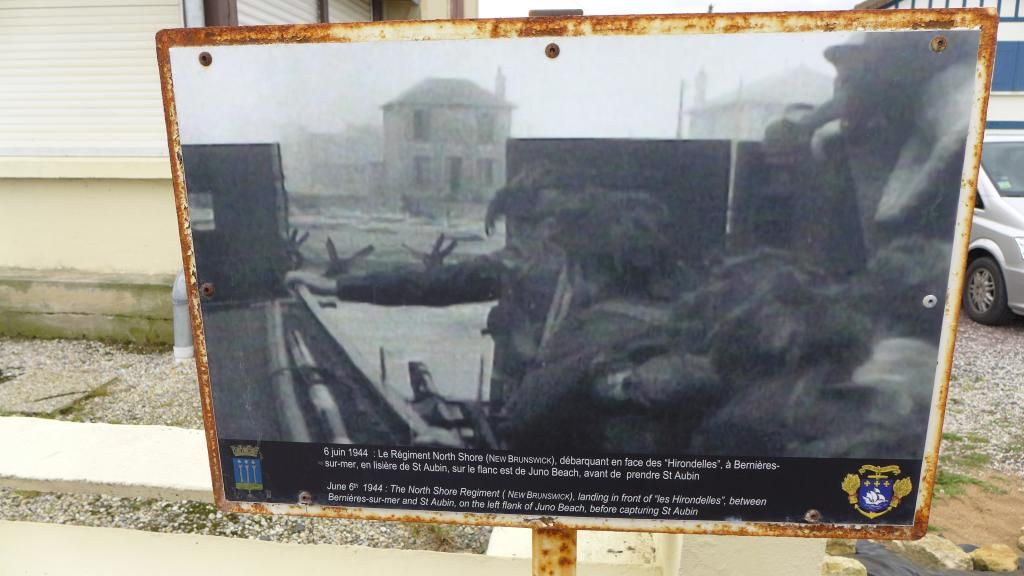

Juno Beach - Courselles - Nan Green sector - Regina Rifles assault & DD Tank Memorial

Juno Beach - Mike Red & Green Sectors - Royal Winnipeg Rifles/Canadian Scottish & AVRE Tank Memorial &

Cross of Lorraine & Polish Memorial

Gold Beach - King Green/Red - Sector La Paisty Vert - Mont Fleury Battery Stanley Hollis VC action

Gold Beach - Asnelles/Le Hamel - British 50th Infantry Division/231 Brigade assault - view of Mulberry Harbour

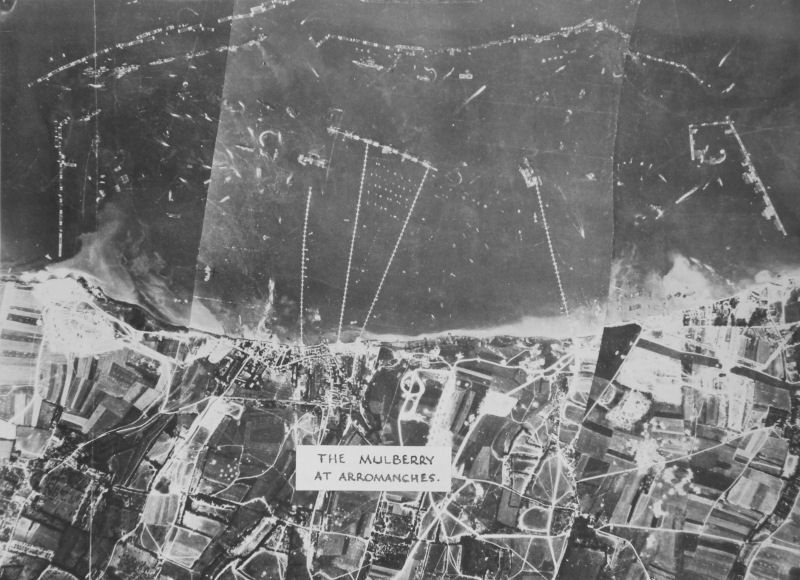

Gold Beach - Arromanches Mulberry Artificial Harbour - view from cliff top - Radar Station position

We had beautiful weather for Day Four.

It was sunny and cool, just perfect for touring.

Gary didn’t want to start with the British and Canadian Beaches in the morning, the tides were not right.

We would, instead head over to the beaches after lunch when the tides were low. He especially wanted to get to Gold Beach at the lowest tide for the best view of the Mulberry Harbor (which was incedible).

So we started off at other points of interest.

The first site was the Chateau where Montgomery made the 21st Army Group HQ.

British forces landing at Sword Beach in Normandy made rapid progress and within days General Montgomery established his HQ in this exquisite châteaux at Creully.

Commanded by General (later Field Marshal) Sir Bernard Montgomery, 21st Army Group initially controlled all ground forces in Operation Overlord (the United States First Army and British Second Army). When sufficient American forces had landed, their own 12th Army Group was activated, under General Omar Bradley, and the 21st Army Group was left with the British Second Army and the newly activated First Canadian Army.

Headquarters 21st Army Group was a very large and complex organisation. In common with most headquarters it consisted of a small Tactical Headquarters, a larger Main Headquarters and a larger still Rear Headquarters.

Tactical Headquarters contained only those personnel which were needed for the command of the organisation. Here were General (later Field Marshall) Montgomery and his personal staff. Gathered around the headquarters were defence troops, Phantom (GHQ Liaison Regiment), Signals and other essentials, but none of the Staff and Headquarters personnel who remained many miles to the rear. Tactical Headquarters was as far forward as was practical and was usually under canvas and thus ready to move at short notice.

Main Headquarters was the home of the General Staff where detailed planning and staff work concerned with operations was carried out. The Chief of Staff commanded Main Headquarters and was a frequent visitor at Tactical Headquarters. Usually this large concentration of key staff officers was located well to the rear and whenever possible it was housed in permanent buildings.

Rear Headquarters contained the staff of the ‘A’ and ‘Q’ branches as well as the staff of the various services and departments. The detailed work of supplying and maintaining the Army Group was done here. Much of the work was routine and went on regardless of operations but clearly operations depended to some extent on the work done at Rear Headquarters. Usually this headquarters was located far to the rear and in permanent accommodation.

(Thanks to Trux at 2talk.com)

HQ Location in Normandy (about dead center of Sword, Juno and Gold beaches:

The fighting around the chateaus was tremendous.

Many tanks were knocked out trying to cross the small bridge:

The HQ:

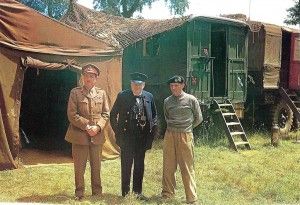

Montgomery did not actually stay in the house he stayed in a caravan on the grounds.

(It drove his commando protection group crazy)

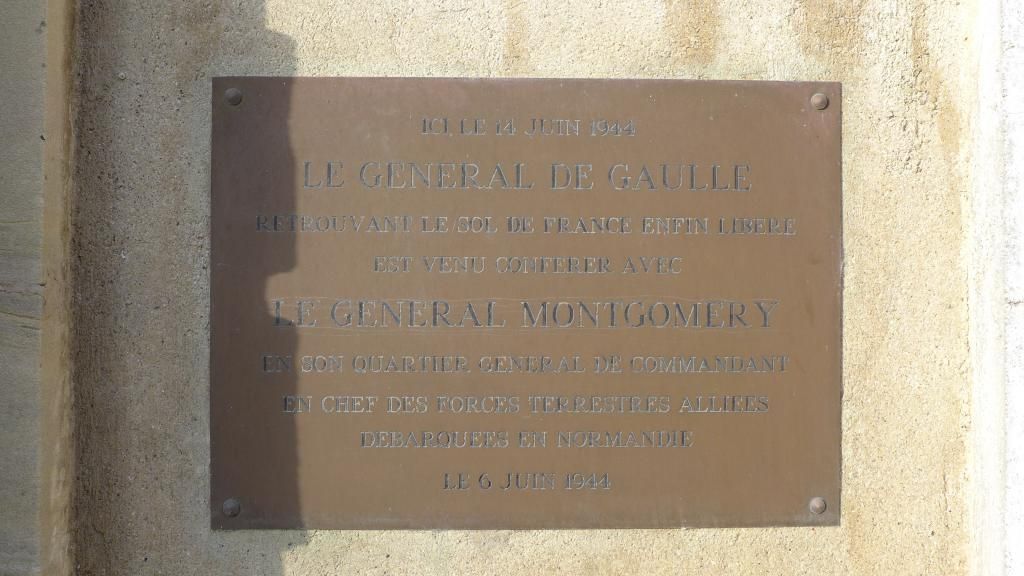

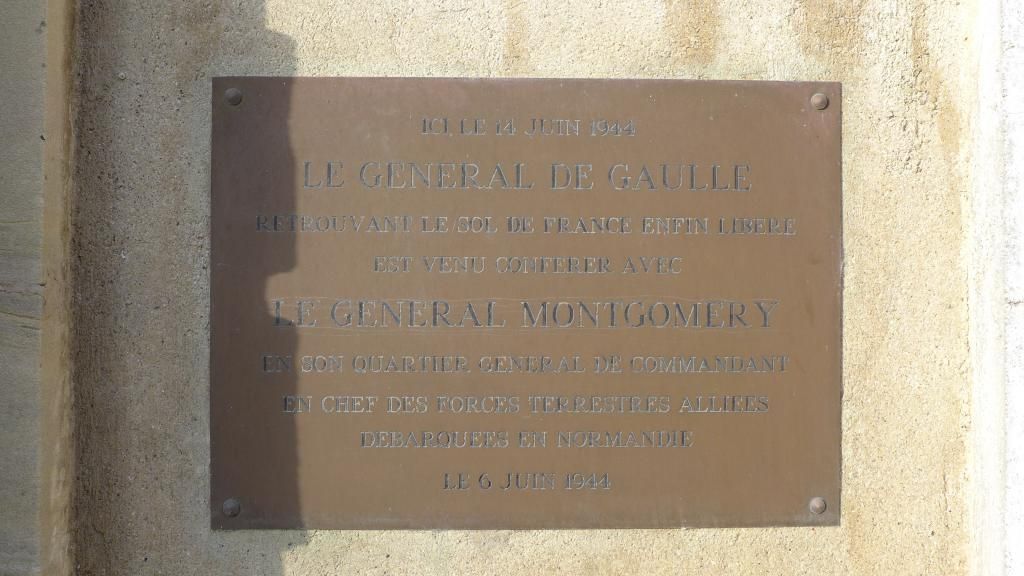

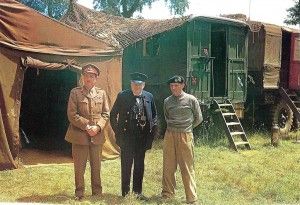

Many heads of state and high ranked generals met here with Montgomery.

Field-Marshal-Sir-Alan-Brooke-Chief-of-the-Imperial-General-Staff-Mr.-Winston-Churchill-and-General-Sir-Bernard-Montgomery-at-21-Army-Group-Headquarters-in-Normandy

Churchill petting Montgomery's dog (Named Rommel)

General_Montgomery_with_Generals_Patton_(left)_and_Bradley_(centre)_at_21st_Army_Group_HQ,_Normandy,_7_July_1944._B6551

The far older original châteaux in the town was used by the BBC for its Normandy broadcasts and has one of the world's most important collection of old radio sets.

(From Wikipedia)

The Château de Creully is an 11th- and 12th-century castle located in the town of Creully in the Calvados département of France.

The castle has been modified throughout its history. Around 1050, it did not resemble a defensive fortress but a large agricultural domain. In about 1360, with the Hundred Years War, it was modified into a fortress. During this period, its architecture was demolished and reconstructed with each occupation by the English and the French:

The square tower was built in the 14th century

A watchtower was added in the 15th century

Drawbridge in front of the keep (removed later in 16th century)

Fortification of the walls and demolition of other buildings likely to pose a danger to besieged inhabitants (stables, depots, outside kitchens).

With the end of the war (1450), ownership of the castle returned to baron de Creully. It was demolished on the orders of Louis XI in 1461 through plain jealousy. According to legend, When Louis XI passed through Creully in 1471 he authorised its rebuilding to thank the local people for their warm welcome.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the barons made modifications:

Filling of the interior ditch and destruction of the drawbridge

Construction of a Renaissance style turret and large windows

Outbuildings, originally stables, added in 17th

Twenty two barons of the same family had succeeded to the castle between 1035 and 1682. In 1682, the last baron of Creully, Antoine V de Sillans, heavily indebted, sold the castle to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister of Louis XIV, who died the following year without living there. Descendants of Colbert occupied Creully until the French Revolution in 1789, when it was confiscated and sold to various rich landowners.

In 1946, the commune of Creully became the owner of part of the site. The castle's large halls are used today for various events, including weddings, concerts, exhibitions and conferences. The site is classified as a monument historique.

Second World War[edit]

From 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, until 21 July, the square tower housed the BBC war correspondents and their radio studio, whence the first news of the Battle of Normandy was transmitted. From 8 June[1] to 2 August 1944,[2] Field Marshal Montgomery had his tactical headquarters at the château. Prime Minister Churchill visited him there.

Gary said that the chateau would have been bristling with antenna during the Battle of Normandy.

He also knows the owner and has been to see the large amount of rare radio equipment housed in the tower.

This is the view from the gate area of the HQ. You can see the Chateau in the background center.

The small bridge fought for is on the left and the row of trees in front where the German positions were.

(Gary, in front, is decscribing the action)

A view of the chateau from the hedge:

A view from the street below.

The tower on the right held the radio equipment.

A view from the opposite side and from the court yard:

(I left out the moat and draw bridge which were quite nice really)

Creully - 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial - DD Tanks

Just below the chateua is a memorial for the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards

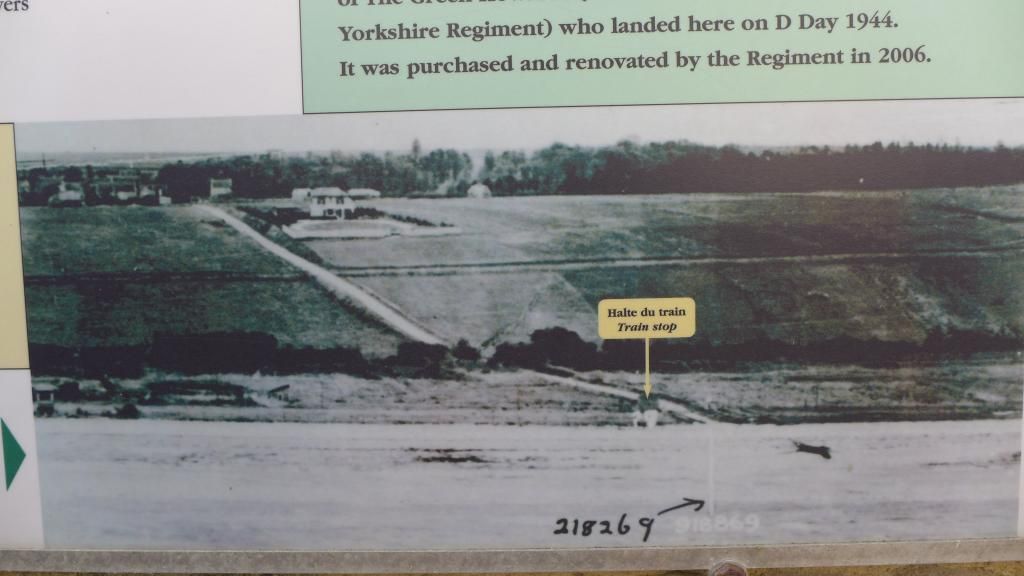

On 6th June, 1944 - D-Day - the Regiment, now part of the 8th Armoured Brigade, landed on GOLD BEACH in Normandy, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadron landing 5 minutes before H (attack) Hour at 0720 Hrs in amphibious D D Sherman tanks. On the first day ‘A’ Squadron with the 7th Battalion Green Howards following a route through CREPON liberated CREULLY. This small town is where the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial is situated. The Regiment took part in the bitter fighting at CRISTOT against elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

Canadian Cemetery

The Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery is a cemetery containing predominantly Canadian soldiers killed during the early stages of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. It is located in and named after Bény-sur-Mer in the Calvados department, near Caen in lower Normandy. As is typical of war cemeteries in France, the grounds are beautifully landscaped and immaculately kept. Contained within the cemetery is a Cross of Sacrifice, a piece of architecture typical of memorials designed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Canadian soldiers killed later in the Battle of Normandy are buried south east of Caen in the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery located in Cintheaux.

Bény-sur-Mer was created as a permanent resting place for Canadian soldiers who had been temporarily interred in smaller plots close to where they fell. As is usual for war cemeteries or monuments, France granted Canada a perpetual concession to the land occupied by the cemetery. The graves contain soldiers from the 3rd Canadian Division and 15 airmen killed during the Battle of Normandy.

The cemetery also includes four British graves and one French grave, for a total of 2048 markers. The French grave belongs to a French resistance soldier named R. Guenard who fought and died alongside the Canadians and who had no known relatives. His marker is the grey cross visible in the lower left of the panoramic view below and is inscribed "Mort pour la France- 19-7-1944".

Because of confusion during the movement of remains from temporary cemeteries, the remains of one Canadian soldier were misplaced; his tombstone is set apart from the others, and bears an inscription stating that it is known that his remains are in the Bény-sur-Mer cemetery. Bény-sur-Mer contains the remains of nine sets of brothers, a record for a Second World War cemetery.

A large number of dead in the cemetery were killed in early July 1944 in the Battle for Caen. The cemetery also contains soldiers who fell during the initial D-Day assault of Juno Beach. The Canadian Prisoners of War illegally executed at the Ardenne Abbey are interred here. It also contains the grave of Rev. (H/Capt) Walter Brown, chaplain to the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers) and the only chaplain killed in cold blood during the Second World War. Rev Brown was murdered on the night of June 6/7 by members of III/25th SS Panzer Grenedier Regt near Galmanche, but his body was not found until July 1944. Canadians killed later in the campaign were interred in the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery. (Wikipedia)

Gary pointed out that unlike other cemeteries the Canadians keep something growing that is colorful all year round.

Of course we stopped at a few grave sites and spoke of who was buried there and what they did in Normandy.

All very moving.

The entrance:

When the plants stop blooming they are removed and replaced with flowering ones.

There is only one cross in the cemetery.

That of Mr. R. Guenard. He was in the resistance and was helping the Canadians when he was killed.

Gary says it probably wasn't his real name. The resistance fighters never used their real name for rear of retribution on their families.

Grave of Mr. R. Guenard

(May he rest in peace)

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

I see some of the pictures have issues.

I'll fix those at a later date...

I hope you enjoy the tour

Day 4 - British & Canadian Beaches plus other sites

Creully - Chateau de Creullet - Montgomery's 21st Army Group Headquarters

Creully - 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial - DD Tanks & Chateau de Creully BBC HQ

Reviers - Neolithic Barrow Fort

Beny-sur-Mer - Canadian Military Cemetery Periers Ridge - Overlooking Sword Beach - route of 21st Panzer Division counter-attack on D-Day

Periers Ridge - Royal Norfolk Regiment Monument - Belvoir Farm

'Hillman' Strongpoint - Colonel Ludwig Krug's HQ taken by 1 Suffolks

Lunch - Hermanville-sur-Mer

Sword Beach - Queen White - Hermanville - Assault area of British 3rd Infantry Division & Memorials

Sword Beach - Lion-sur-Mer - AVRE Tank (Petard Mortar) & Memorials for 41 Commando and Roosevelt

Juno Beach - Courselles - Nan Green sector - Regina Rifles assault & DD Tank Memorial

Juno Beach - Mike Red & Green Sectors - Royal Winnipeg Rifles/Canadian Scottish & AVRE Tank Memorial &

Cross of Lorraine & Polish Memorial

Gold Beach - King Green/Red - Sector La Paisty Vert - Mont Fleury Battery Stanley Hollis VC action

Gold Beach - Asnelles/Le Hamel - British 50th Infantry Division/231 Brigade assault - view of Mulberry Harbour

Gold Beach - Arromanches Mulberry Artificial Harbour - view from cliff top - Radar Station position

We had beautiful weather for Day Four.

It was sunny and cool, just perfect for touring.

Gary didn’t want to start with the British and Canadian Beaches in the morning, the tides were not right.

We would, instead head over to the beaches after lunch when the tides were low. He especially wanted to get to Gold Beach at the lowest tide for the best view of the Mulberry Harbor (which was incedible).

So we started off at other points of interest.

The first site was the Chateau where Montgomery made the 21st Army Group HQ.

British forces landing at Sword Beach in Normandy made rapid progress and within days General Montgomery established his HQ in this exquisite châteaux at Creully.

Commanded by General (later Field Marshal) Sir Bernard Montgomery, 21st Army Group initially controlled all ground forces in Operation Overlord (the United States First Army and British Second Army). When sufficient American forces had landed, their own 12th Army Group was activated, under General Omar Bradley, and the 21st Army Group was left with the British Second Army and the newly activated First Canadian Army.

Headquarters 21st Army Group was a very large and complex organisation. In common with most headquarters it consisted of a small Tactical Headquarters, a larger Main Headquarters and a larger still Rear Headquarters.

Tactical Headquarters contained only those personnel which were needed for the command of the organisation. Here were General (later Field Marshall) Montgomery and his personal staff. Gathered around the headquarters were defence troops, Phantom (GHQ Liaison Regiment), Signals and other essentials, but none of the Staff and Headquarters personnel who remained many miles to the rear. Tactical Headquarters was as far forward as was practical and was usually under canvas and thus ready to move at short notice.

Main Headquarters was the home of the General Staff where detailed planning and staff work concerned with operations was carried out. The Chief of Staff commanded Main Headquarters and was a frequent visitor at Tactical Headquarters. Usually this large concentration of key staff officers was located well to the rear and whenever possible it was housed in permanent buildings.

Rear Headquarters contained the staff of the ‘A’ and ‘Q’ branches as well as the staff of the various services and departments. The detailed work of supplying and maintaining the Army Group was done here. Much of the work was routine and went on regardless of operations but clearly operations depended to some extent on the work done at Rear Headquarters. Usually this headquarters was located far to the rear and in permanent accommodation.

(Thanks to Trux at 2talk.com)

HQ Location in Normandy (about dead center of Sword, Juno and Gold beaches:

The fighting around the chateaus was tremendous.

Many tanks were knocked out trying to cross the small bridge:

The HQ:

Montgomery did not actually stay in the house he stayed in a caravan on the grounds.

(It drove his commando protection group crazy)

Many heads of state and high ranked generals met here with Montgomery.

Field-Marshal-Sir-Alan-Brooke-Chief-of-the-Imperial-General-Staff-Mr.-Winston-Churchill-and-General-Sir-Bernard-Montgomery-at-21-Army-Group-Headquarters-in-Normandy

Churchill petting Montgomery's dog (Named Rommel)

General_Montgomery_with_Generals_Patton_(left)_and_Bradley_(centre)_at_21st_Army_Group_HQ,_Normandy,_7_July_1944._B6551

The far older original châteaux in the town was used by the BBC for its Normandy broadcasts and has one of the world's most important collection of old radio sets.

(From Wikipedia)

The Château de Creully is an 11th- and 12th-century castle located in the town of Creully in the Calvados département of France.

The castle has been modified throughout its history. Around 1050, it did not resemble a defensive fortress but a large agricultural domain. In about 1360, with the Hundred Years War, it was modified into a fortress. During this period, its architecture was demolished and reconstructed with each occupation by the English and the French:

The square tower was built in the 14th century

A watchtower was added in the 15th century

Drawbridge in front of the keep (removed later in 16th century)

Fortification of the walls and demolition of other buildings likely to pose a danger to besieged inhabitants (stables, depots, outside kitchens).

With the end of the war (1450), ownership of the castle returned to baron de Creully. It was demolished on the orders of Louis XI in 1461 through plain jealousy. According to legend, When Louis XI passed through Creully in 1471 he authorised its rebuilding to thank the local people for their warm welcome.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the barons made modifications:

Filling of the interior ditch and destruction of the drawbridge

Construction of a Renaissance style turret and large windows

Outbuildings, originally stables, added in 17th

Twenty two barons of the same family had succeeded to the castle between 1035 and 1682. In 1682, the last baron of Creully, Antoine V de Sillans, heavily indebted, sold the castle to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister of Louis XIV, who died the following year without living there. Descendants of Colbert occupied Creully until the French Revolution in 1789, when it was confiscated and sold to various rich landowners.

In 1946, the commune of Creully became the owner of part of the site. The castle's large halls are used today for various events, including weddings, concerts, exhibitions and conferences. The site is classified as a monument historique.

Second World War[edit]

From 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, until 21 July, the square tower housed the BBC war correspondents and their radio studio, whence the first news of the Battle of Normandy was transmitted. From 8 June[1] to 2 August 1944,[2] Field Marshal Montgomery had his tactical headquarters at the château. Prime Minister Churchill visited him there.

Gary said that the chateau would have been bristling with antenna during the Battle of Normandy.

He also knows the owner and has been to see the large amount of rare radio equipment housed in the tower.

This is the view from the gate area of the HQ. You can see the Chateau in the background center.

The small bridge fought for is on the left and the row of trees in front where the German positions were.

(Gary, in front, is decscribing the action)

A view of the chateau from the hedge:

A view from the street below.

The tower on the right held the radio equipment.

A view from the opposite side and from the court yard:

(I left out the moat and draw bridge which were quite nice really)

Creully - 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial - DD Tanks

Just below the chateua is a memorial for the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards

On 6th June, 1944 - D-Day - the Regiment, now part of the 8th Armoured Brigade, landed on GOLD BEACH in Normandy, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadron landing 5 minutes before H (attack) Hour at 0720 Hrs in amphibious D D Sherman tanks. On the first day ‘A’ Squadron with the 7th Battalion Green Howards following a route through CREPON liberated CREULLY. This small town is where the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards Memorial is situated. The Regiment took part in the bitter fighting at CRISTOT against elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

Canadian Cemetery

The Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery is a cemetery containing predominantly Canadian soldiers killed during the early stages of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. It is located in and named after Bény-sur-Mer in the Calvados department, near Caen in lower Normandy. As is typical of war cemeteries in France, the grounds are beautifully landscaped and immaculately kept. Contained within the cemetery is a Cross of Sacrifice, a piece of architecture typical of memorials designed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Canadian soldiers killed later in the Battle of Normandy are buried south east of Caen in the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery located in Cintheaux.

Bény-sur-Mer was created as a permanent resting place for Canadian soldiers who had been temporarily interred in smaller plots close to where they fell. As is usual for war cemeteries or monuments, France granted Canada a perpetual concession to the land occupied by the cemetery. The graves contain soldiers from the 3rd Canadian Division and 15 airmen killed during the Battle of Normandy.

The cemetery also includes four British graves and one French grave, for a total of 2048 markers. The French grave belongs to a French resistance soldier named R. Guenard who fought and died alongside the Canadians and who had no known relatives. His marker is the grey cross visible in the lower left of the panoramic view below and is inscribed "Mort pour la France- 19-7-1944".

Because of confusion during the movement of remains from temporary cemeteries, the remains of one Canadian soldier were misplaced; his tombstone is set apart from the others, and bears an inscription stating that it is known that his remains are in the Bény-sur-Mer cemetery. Bény-sur-Mer contains the remains of nine sets of brothers, a record for a Second World War cemetery.

A large number of dead in the cemetery were killed in early July 1944 in the Battle for Caen. The cemetery also contains soldiers who fell during the initial D-Day assault of Juno Beach. The Canadian Prisoners of War illegally executed at the Ardenne Abbey are interred here. It also contains the grave of Rev. (H/Capt) Walter Brown, chaplain to the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers) and the only chaplain killed in cold blood during the Second World War. Rev Brown was murdered on the night of June 6/7 by members of III/25th SS Panzer Grenedier Regt near Galmanche, but his body was not found until July 1944. Canadians killed later in the campaign were interred in the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery. (Wikipedia)

Gary pointed out that unlike other cemeteries the Canadians keep something growing that is colorful all year round.

Of course we stopped at a few grave sites and spoke of who was buried there and what they did in Normandy.

All very moving.

The entrance:

When the plants stop blooming they are removed and replaced with flowering ones.

There is only one cross in the cemetery.

That of Mr. R. Guenard. He was in the resistance and was helping the Canadians when he was killed.

Gary says it probably wasn't his real name. The resistance fighters never used their real name for rear of retribution on their families.

Grave of Mr. R. Guenard

(May he rest in peace)

Last edited: