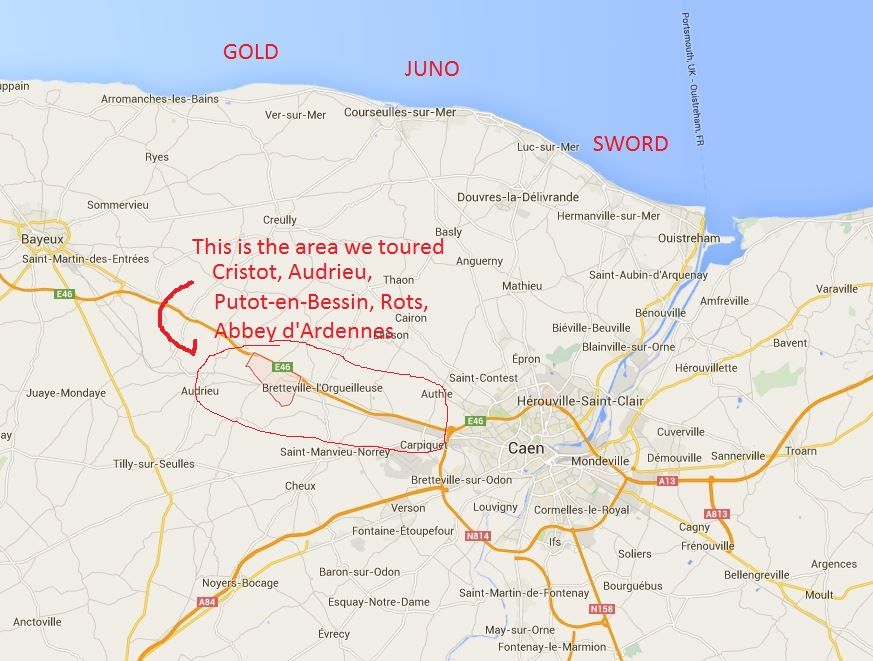

I thought I would revive these for the 75th anniversary of D-Day

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

I see some of the pictures have issues.

I'll fix those at a later date...

I hope you enjoy the tour

Day 5 - Various

Longues-sur-Mer - Gun battery original coastal guns

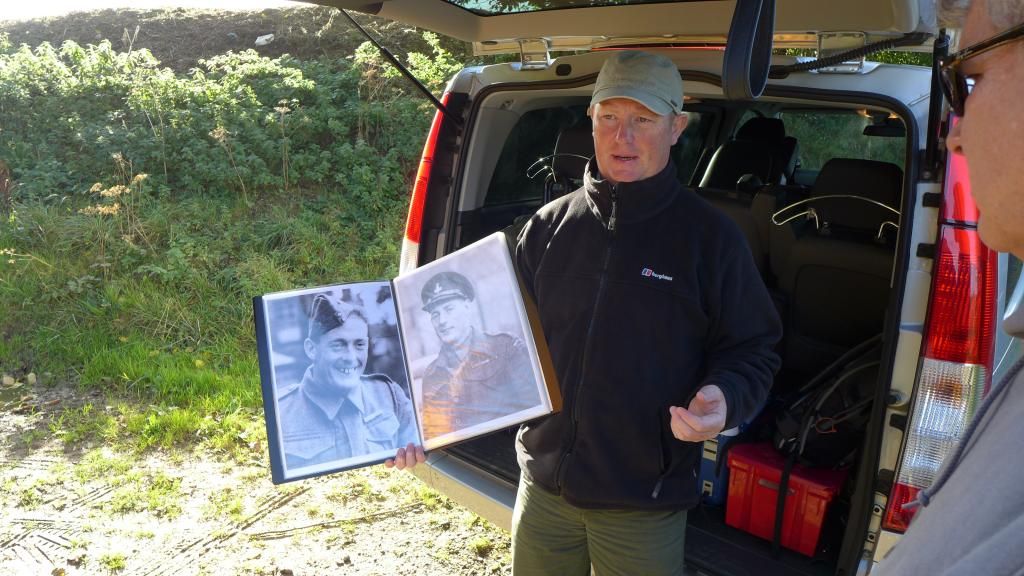

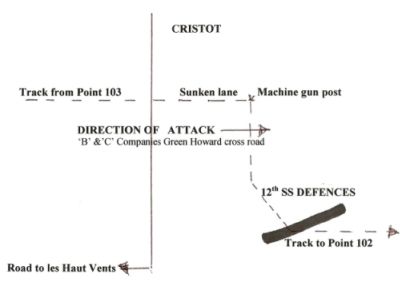

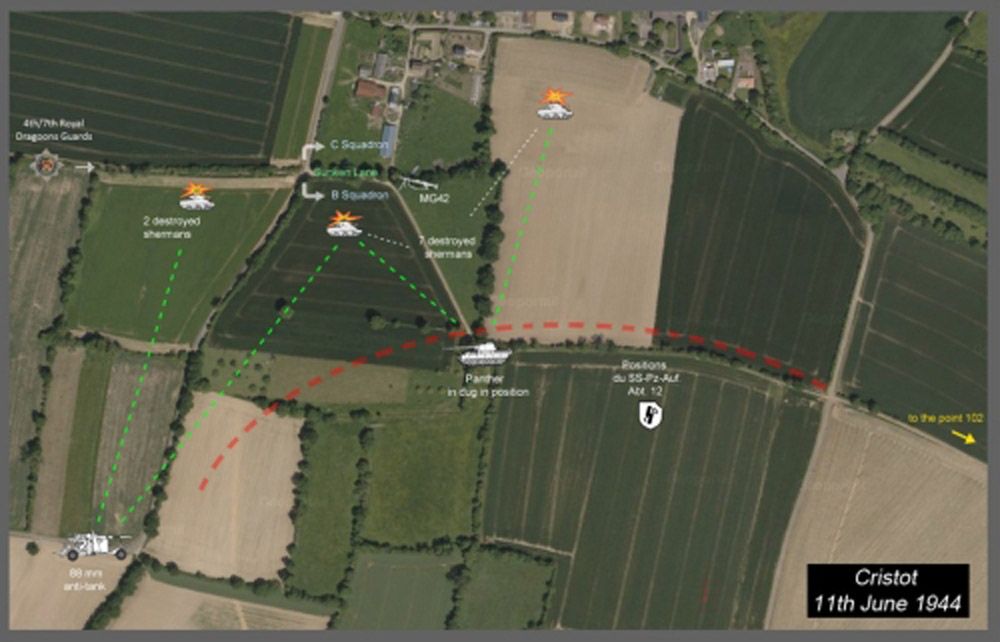

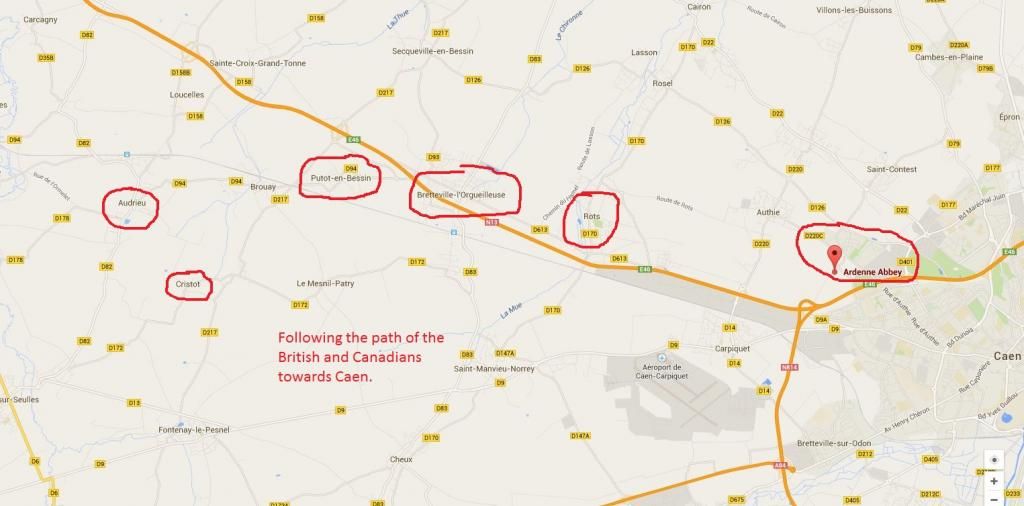

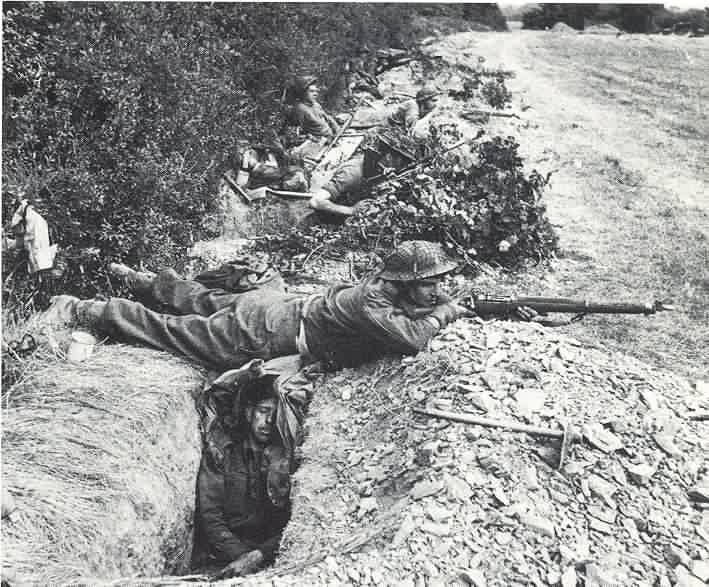

Cristot - Sunken lane CSM Stan Hollis VC action against 12SS

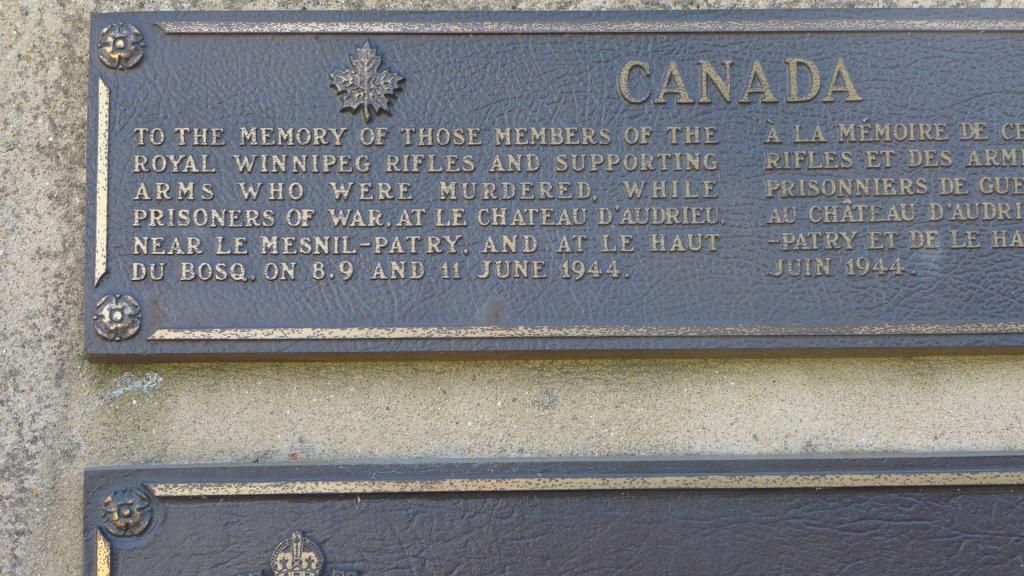

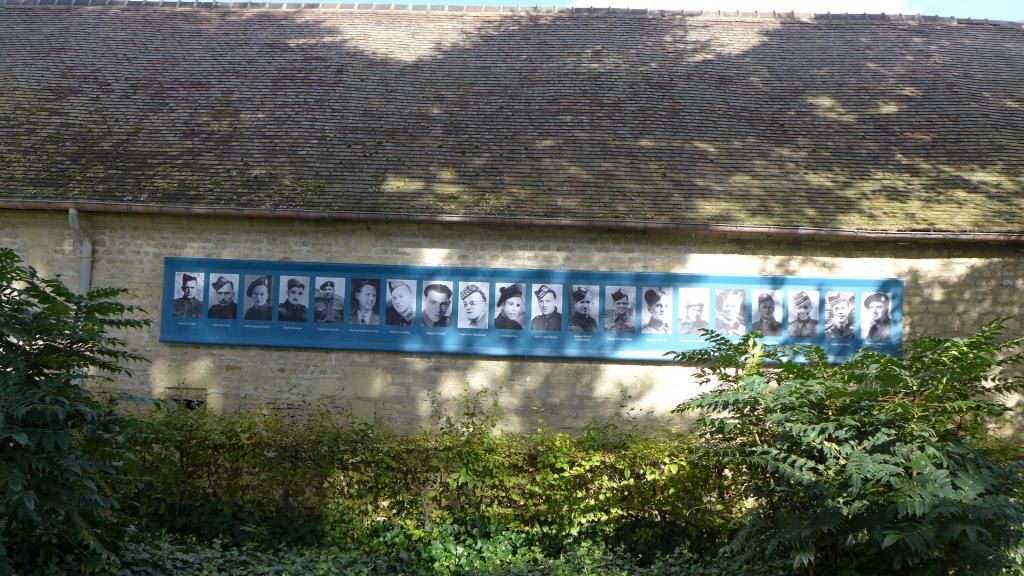

Audrieu - Chateau - HQ 12SS Reconnaissance Battalion - Scene of executions

Audrieu - Monument to the murdered

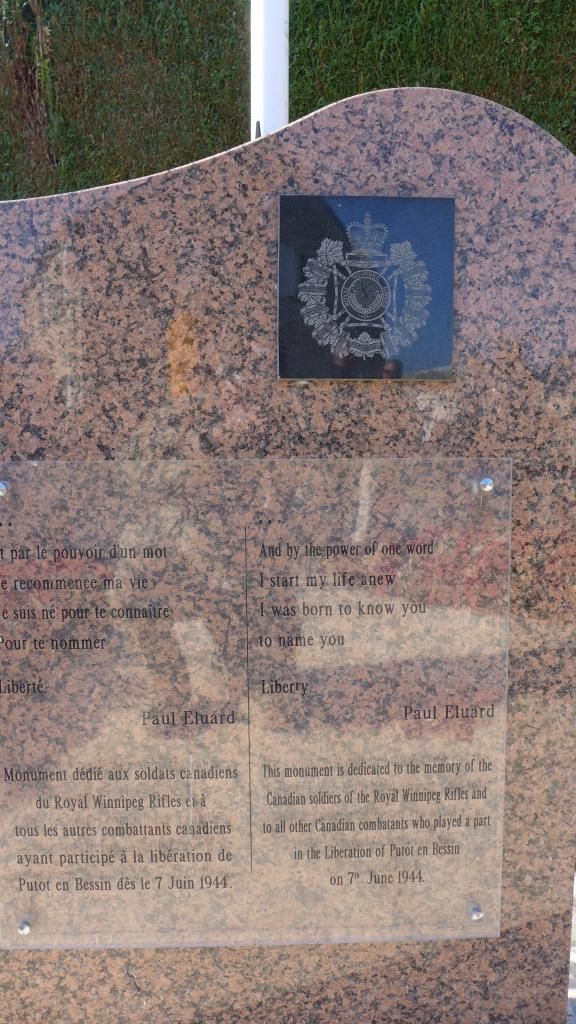

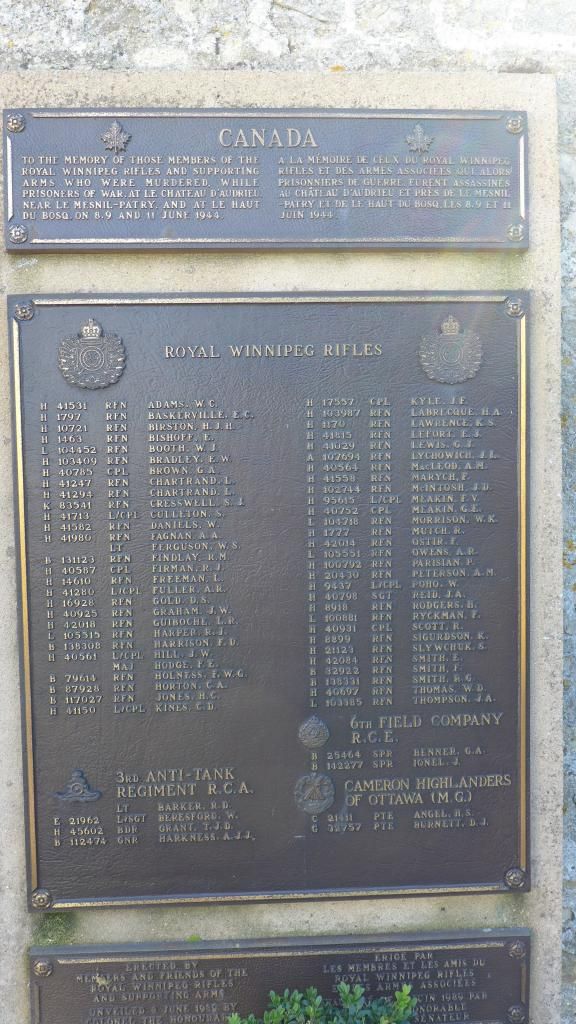

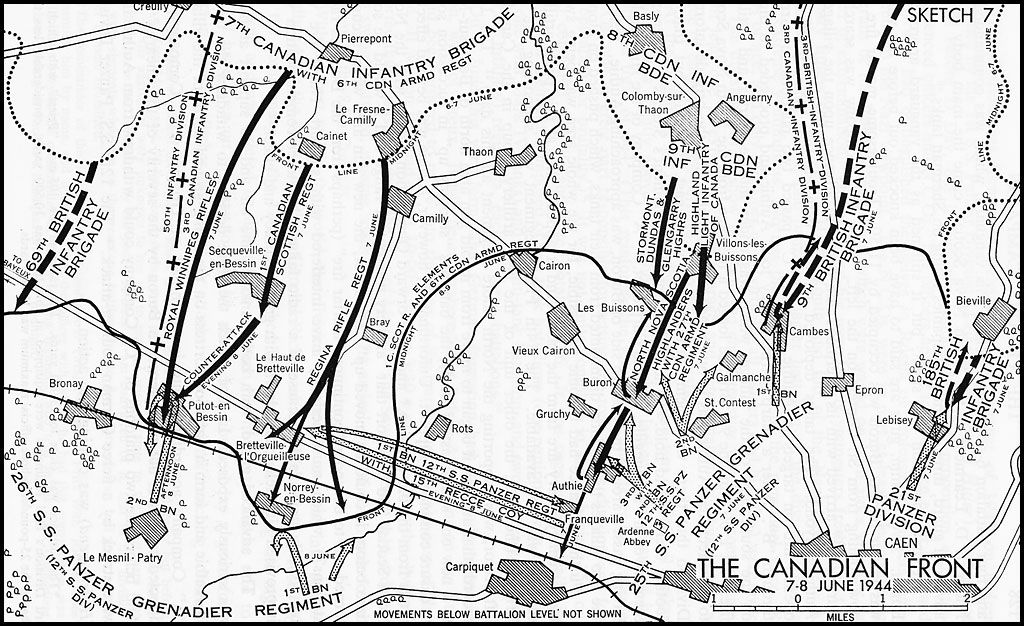

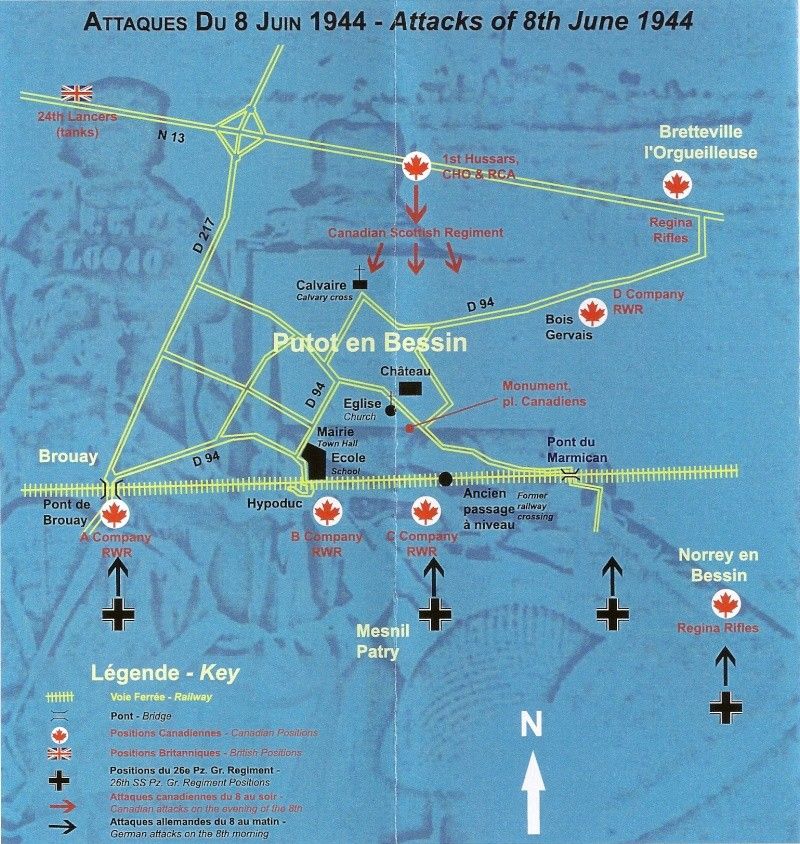

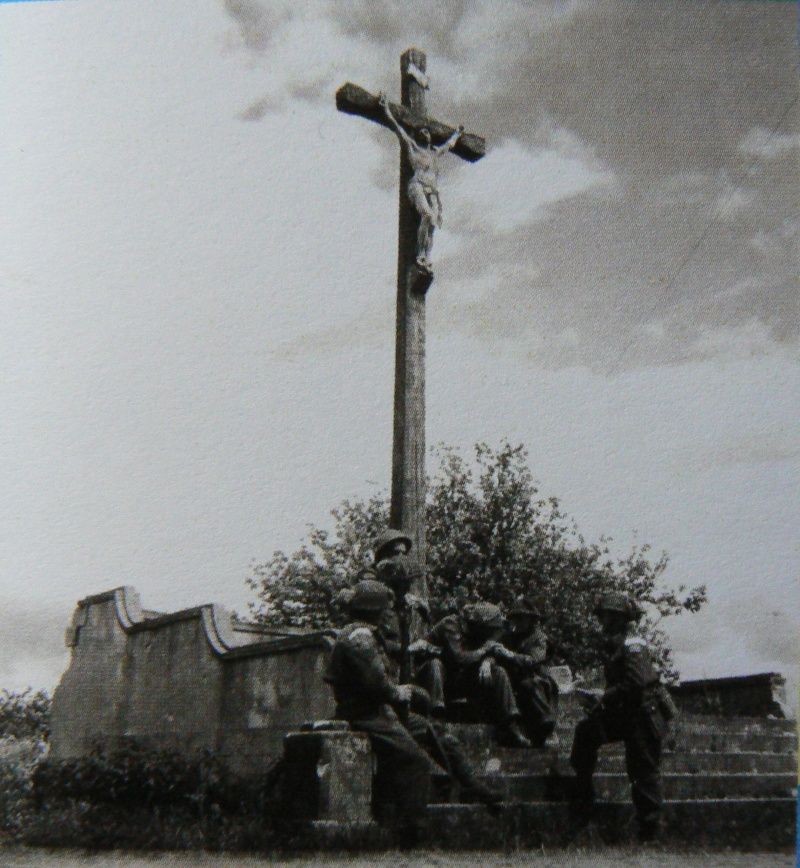

Putot-en-Bessin - Monument in the village to the Canadian units - Royal Winnipeg Rifles and Canadian Scottish

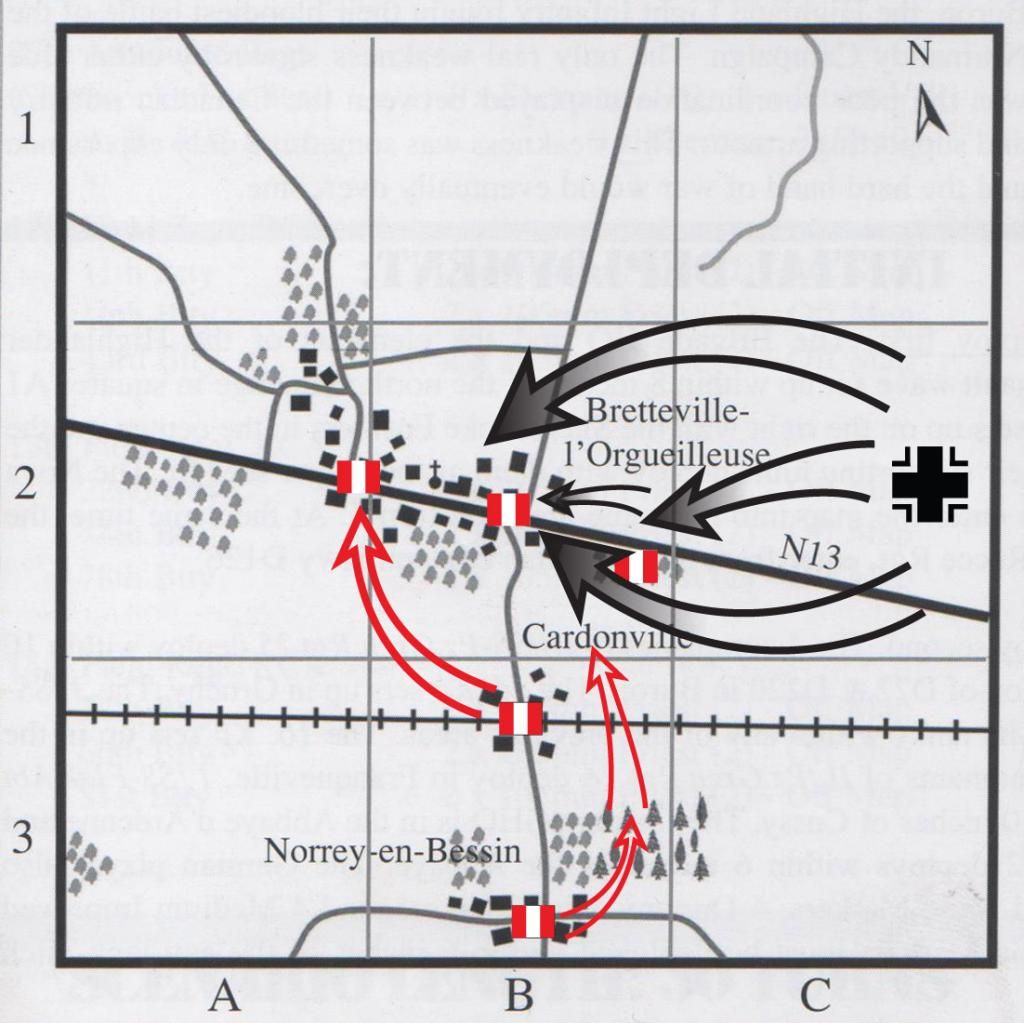

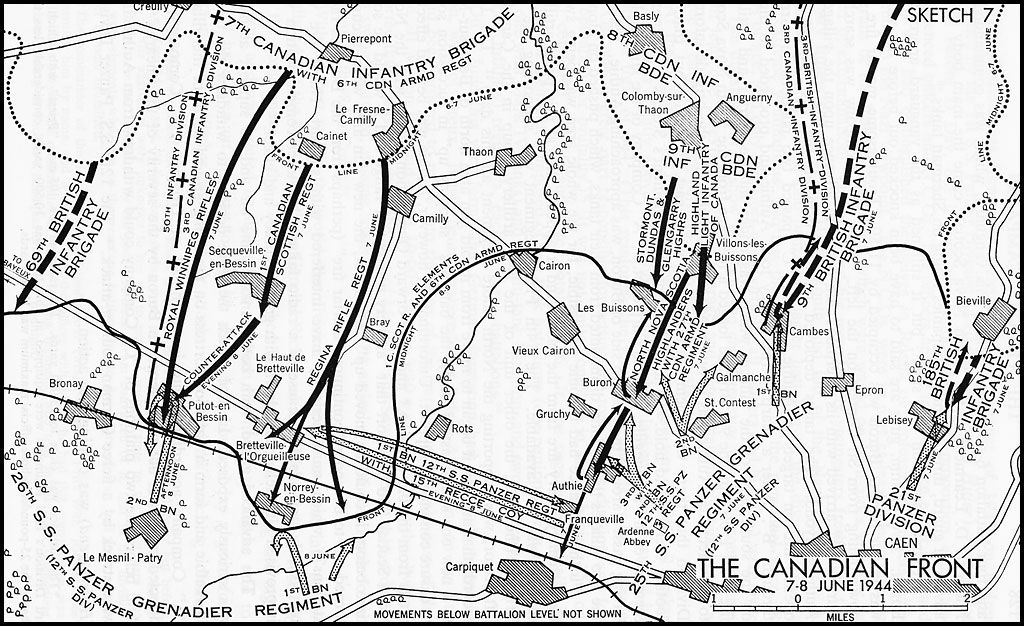

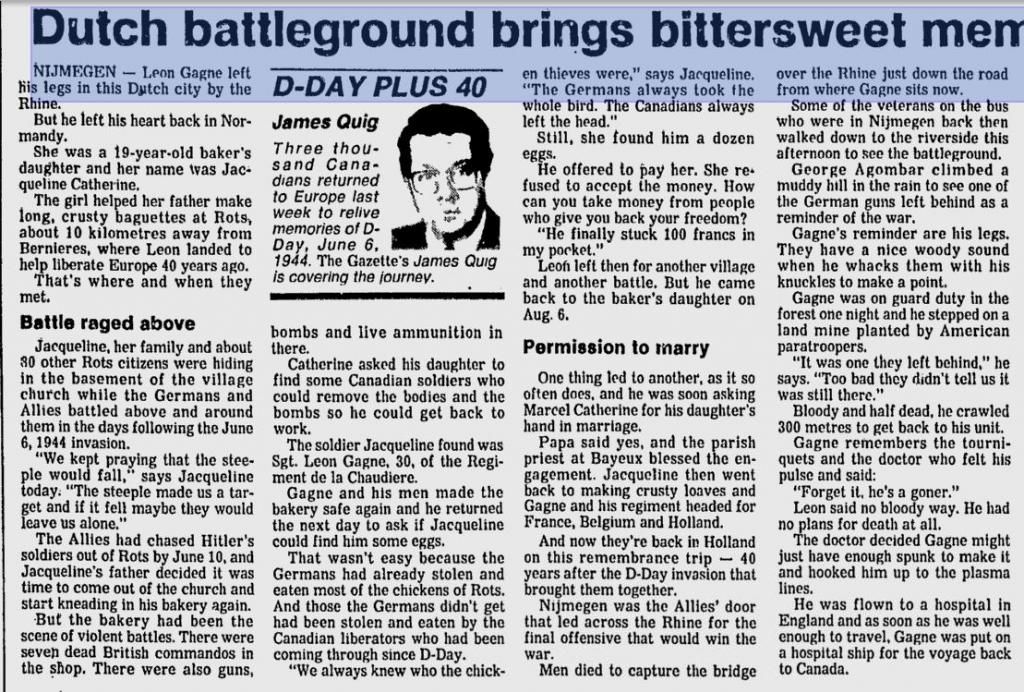

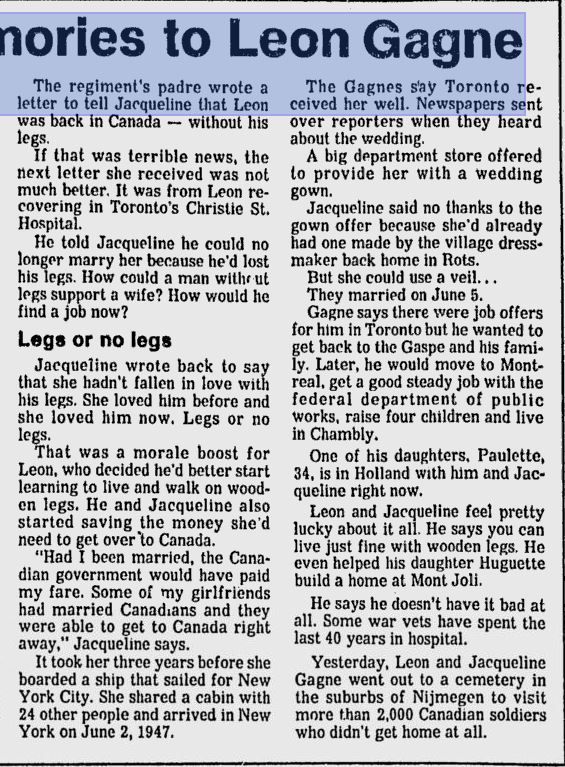

Bretteville L'Orgueilleuse - Regina Rifles/12th SS Panzer Division/knocked out Panther tank and destroyed church

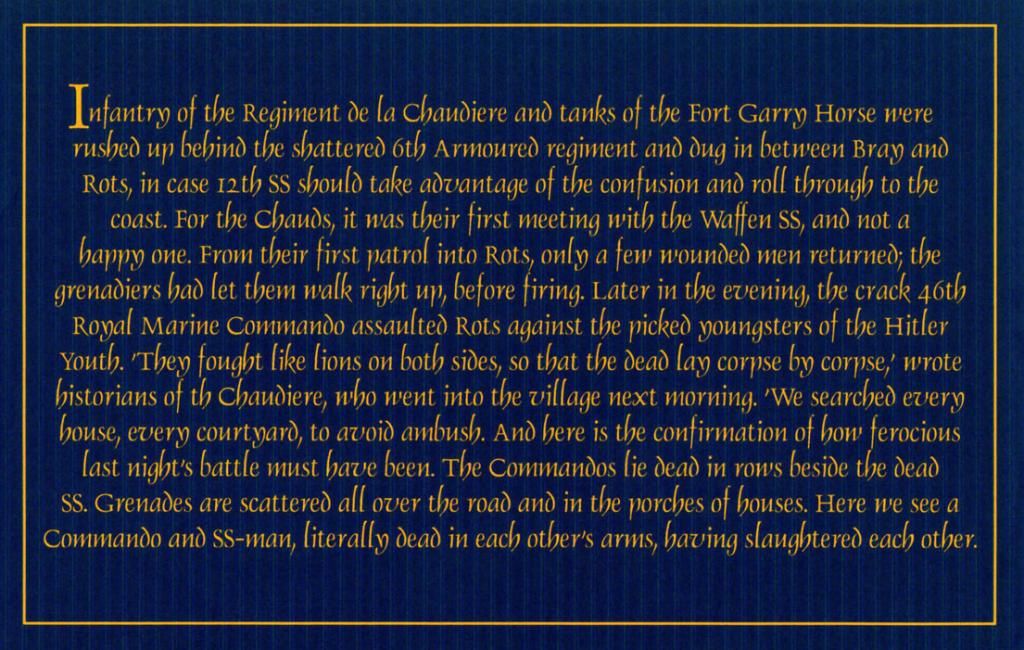

Rots - 46 Commando Memorial

Rots - Canadian Scottish/Chaudiere/Fort Garry Horse Memorial & Passage Leon Gagne (married the bakers

daughter)

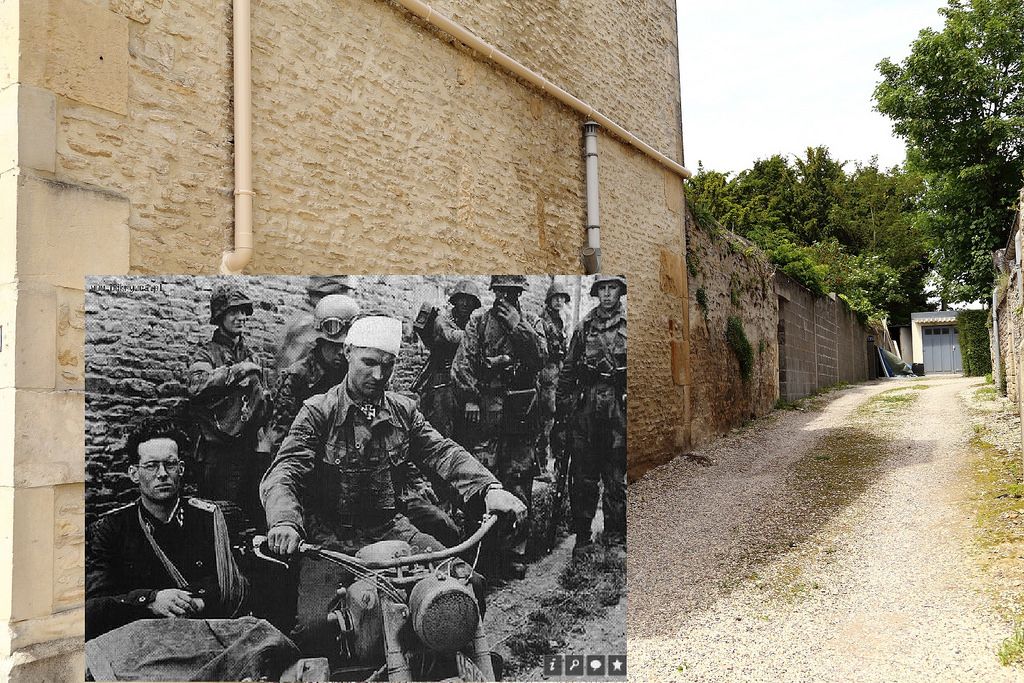

Rots - Church square - tank battles with 12th SS

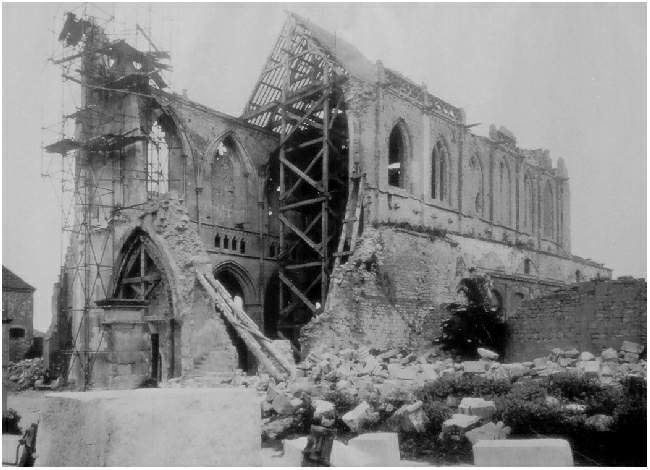

Abbey d'Ardennes - 12th SS Panzer/25th Panzer Grenadiers Regimental HQ - Kurt Meyer - Canadian prisoners

executed 7th (plus other dates) June 1944.

Lunch at Bretteville-sur-Odon

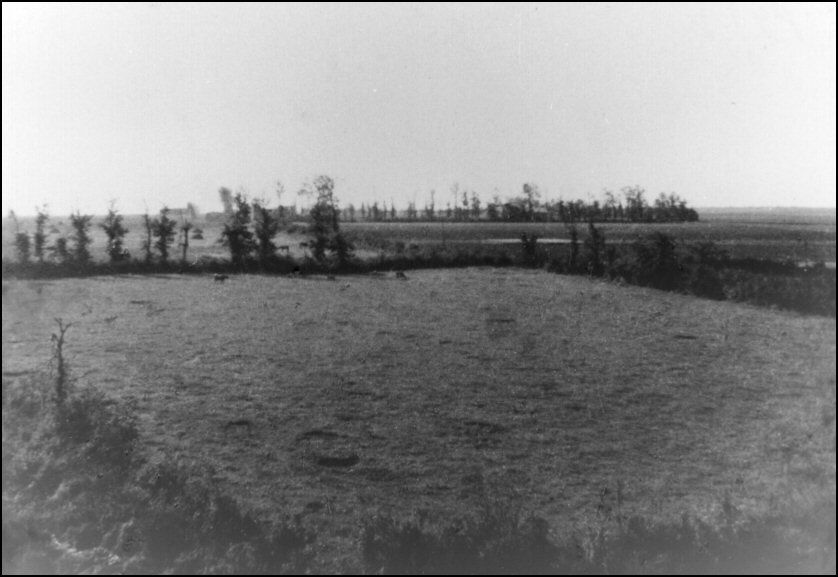

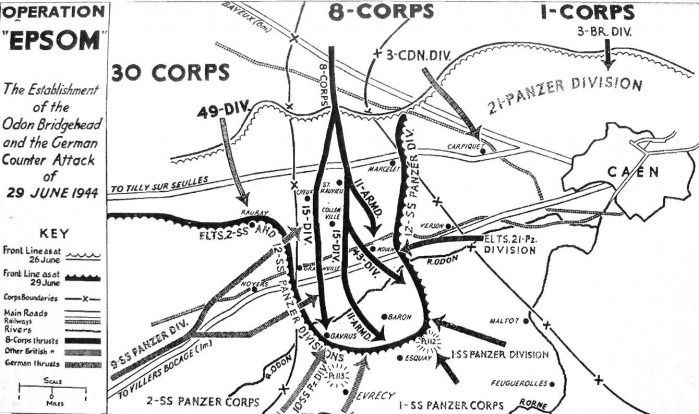

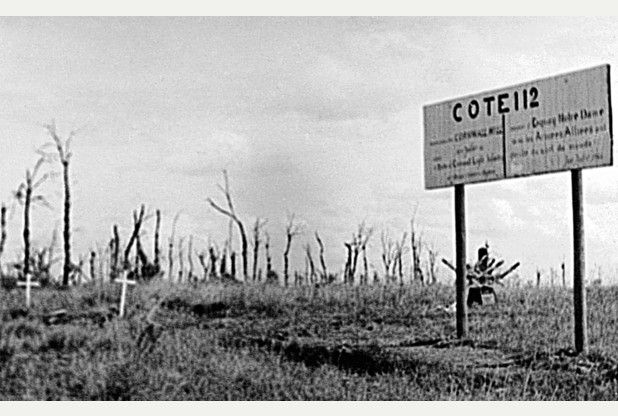

Hill 112 - 43rd Wessex Division v various SS units 1/9/10 and 12

Villers Bocage

Tilly-sur-Seulles - British Cemetery

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(Note-This will be the longest post of Day 5 because there were so many good photo opportunities.)

First thing we did on Day 5 of the tour is head over to the gun battery at Longues-sur-Mer.

This, I would guess, is the best preserved battery in all of Normandy.

But first, right next to the Longues-sur-Mer Battery is a memorial who commerates the Allied airfield (B11) which was in service between 21 June and 4 September 1944. The airfield was located 300 metres east of the battery.

Longues-sur-Mer airfield (Advanced Landing Ground B-11 Longues-sur-Mer) was an airfield on the Normandy beachhead in France, 7 kilometers north of Bayeux.

The airfield became operational on 26 June 1944.

To cover the runway, the British set up anti-aircraft guns on the roof of the Longues-sur-Mer coastal artillery bunker .

Inside the former German bunker they stored the ammunition for the airfield.

An explosion in this makeshift magazine caused the deaths of four soldiers.

The violence of this explosion was so great it led to the total destruction of a blockhouse built by the Germans and a twisted gun barrel in front of the casemate.

The airfield was used by the Royal Air Forces 125 Wing (132 Sqn (RAF), 602Sqn (RAF), 453 Sqn (RAAF), 441Sqn (RCAF).

During their operations from Longues-sur-Mer, both 602Sqn and 453Sqn claimed to have strafed a German staff car.

(The same claim was also made by 412Sqn RCAF)

The attack severely injured Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, who fractured his skull.

Generalfeldmarschall Rommel had to be hospitalised for weeks, keeping him from the battlefield.

This was an area without much bocage and ideal for airfields.

Monument to the fliers of airfield B11

A Spitfire of the Royla Air Force under the protection of apple trees on the airfield ALG B-11 Longues

A picture taken here of the Wing Commander, AG Page, leader of the No. 125 Wing , in the cockpit of a Supermarine Spitfire.

From here we drove over to the battery and started our walk down the path that circles the battery.

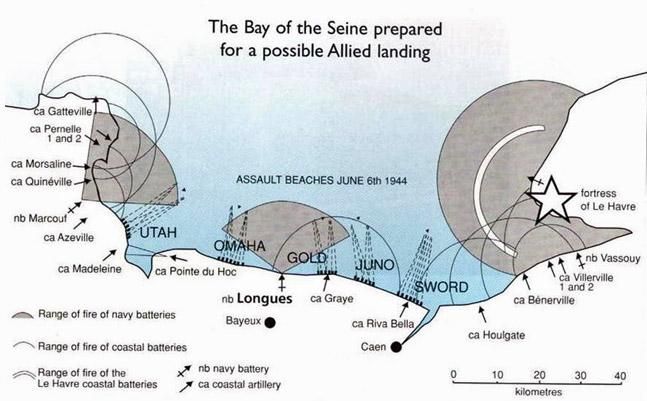

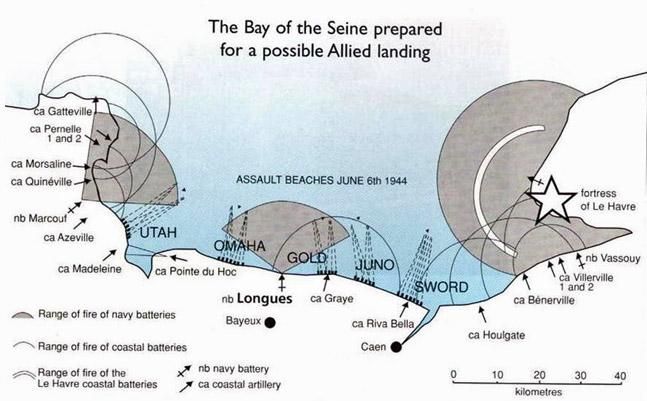

The Longues-sur-Mer battery was a World War II artillery battery constructed by the Wehrmacht near the French village of Longues-sur-Mer in Normandy. It formed a part of Germany's Atlantic Wall coastal fortifications.

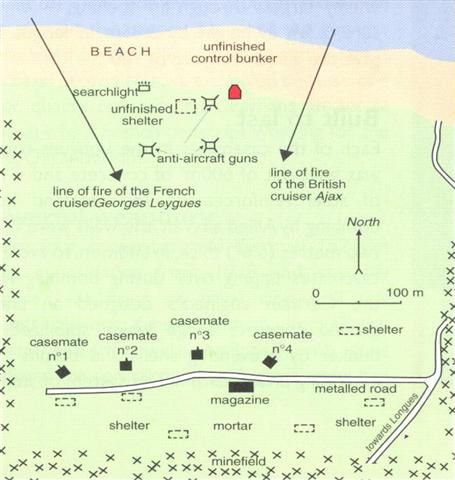

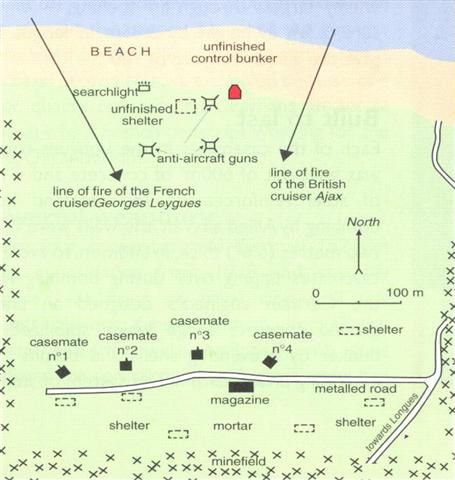

The battery was completed by April 1944. Although constructed and manned initially by the Kriegsmarine, the battery was later transferred to the German army. The site consisted of four 152-mm navy guns, each protected by a large concrete casemate, a command post, shelters for personnel and ammunition, and several defensive machine-gun emplacements.

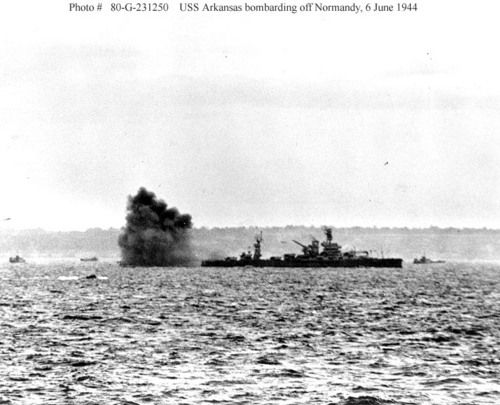

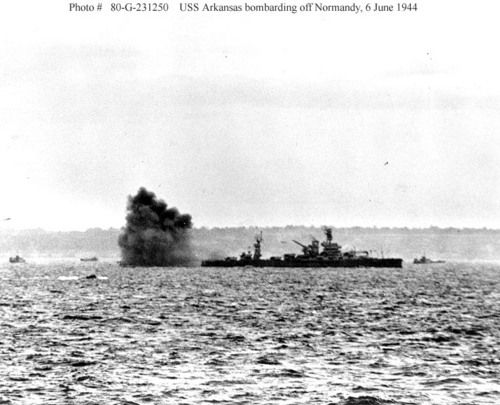

The battery at Longues was situated between the landing beaches Omaha and Gold. On the night before the D-Day landings of 6 June 1944, the battery was subjected to a barrage comprising approximately 1,500 tons of bombs, although much of this landed on a nearby village. The bombing was followed from 0537hrs on the morning of the landings by bombardment from the French cruiser Georges Leygues as well as the U.S. battleship Arkansas. The battery itself opened fire at 0605hrs and fired a total of 170 shots throughout the day, forcing the headquarters ship HMS Bulolo to retreat to safer water. Three of the four guns were eventually disabled by British cruisers Ajax and Argonaut, though a single gun continued to operate intermittently until 1900hrs that evening. The crew of the battery (184 men, half of them over 40 years old) surrendered to the 231st Infantry Brigade the following day.

The heaviest damage was caused by the explosion of the ammunition for an AA gun, mounted by the British on the roof of casemate No.4, which killed several British soldiers.

At 05:30 hrs on D-Day, the batterie was engaged by the French cruiser, FFS Georges Leygues and the American battleship USS Arkansas.The batterie opened fire on the destroyer Emmons stationed off Omaha beach. Due to the fact that the underground cables from the Fire control bunker had been destroyed by the previous bombing raids, the gunners used their direct sights to engage the invasion fleet.

The batterie then engaged the Arkansas..The French cruiser Montcalm also became involved in the exchange of fire.

30 minutes later, the guns then turned their attention to Gold sector and engaged HMS Bulolo, the Gold flagship with the Army Corps commander on board.The accuracy of the batterie forced the ship to weigh anchor. After a further 20 minutes of bombardment, it fell silent.

Ajax was joined by HMS Argonaut in shelling the batterie which was put out of action at 08:45hrs.It had taken 179, 6" and 5.25" shells from the two cruisers. Two of the casemates received direct hits through their embrasures....

The French and the British both claimed the defeat of the batterie as their own....

The two remaining guns opened up again in the late afternoon but were silenced by the French cruiser, FFS Georges Leygues The batterie's 120 survivors out of 184 crew , surrendered the next day to the British 231st Infantry Brigade. The batterie had fired a total of 115 rounds.

(From the Cool Blue Blog)

Here you can get a sense of the results of sea and air bombardment on the battery.

The obeservation bunker is on the left at the edge of the cliff. Two of the batteries are circled.

A closer view:

D-Day Action

There is a degree of controversy between the British and French over the naval engagement of Longues-sur-Mer. However, naval logs of the ships concerned provide a precise record of the action.

At 0500 hours, HMS Ajax was lying at anchor six nautical miles to the north of Longues-sur-Mer. Captain Weld, searching the coastline through his binoculars in the early dawn light, saw the low silhouette of the battery on the cliff top. At 0530 hours (sunrise minus forty minutes) he ordered his eight 6-inch guns to open fire. At first, there was no response. However, the battery opened fire, initially at the destroyer USS Emmons at 0537 hours, but switched its fire to the battleship USS Arkansas lying off Omaha at a range of ten miles.

Arkansas and the French cruiser Georges Leygues joined Ajax’s engagement, firing twenty twelve-inch and one hundred and ten five-inch shells, and the battery fell silent. At 0557, the battery again opened fire, this time to the east, at the anchored HMS Bulolo off Gold, with the first rounds from Number 3 and 4 guns straddling the target.

Bulolo was a prime target, being the Naval Force G’s flagship and 50th Division’s HQ ship and, therefore, a vital nerve centre. She quickly weighed anchor and moved seaward. At 0605 hours Number 1 and 2 guns re-engaged Arkansas and the two French cruisers. In response, FFS Montcalm joined HMS Ajax in her redoubled rate of fire and, by 0620 hours, the battery was again silenced. Over the next two hours, the battery came into action again several times, engaging targets in the Gold area. HMS Argonaut joined Ajax and fired twenty-nine and one hundred and fifty rounds respectively before the battery was silenced at 0845 hours. The guns in casemates 3 and 4 were knocked out, while numbers 1 and 2 were damaged.

By late afternoon, the Kriegsmarine gunners had repaired Number 1 gun, which, because the open front was facing slightly to the west, had been more difficult for Ajax to engage effectively. This gun opened fire on shipping off Omaha, where the battle was only just swinging in the Americans favour.

George Leygues, under command of Naval Bombardment Force C, replied. There was a terse exchange of Aldis Lamp signals between Captain Weld and Admiral Jaujard, the former claiming the battery as Ajax’s exclusive target. The French were not impressed and George Leygues continued to engage! Number 1 gun was finally put out of action at 1800 hours, by the fire of both ships. From the number of empty cylinders in the casemates, it is estimated that the battery fired approximately one hundred and fifty rounds during the course of D-Day. Without the air and naval bombardment, the effect of these shells, and 1,050 rounds found in the battery’s magazines, would have been highly significant, especially off Omaha, where the battle hung in the balance for most of the day.

Commander Edwards attributes Longues-sur-Mer’s neutralisation to some exhibition shooting on the part of Ajax, which will long be quoted as an instance of amazing gunnery by a ship against a shore battery. 2 Devon’s ground attack planned for D-Day did not take place as scheduled. The delay on the beach and more determined resistance than expected caused the battalion to halt at Ryes for the night.

HMS Ajax on D-Day against Longues-sur-Mer Battery.

The Attack on D+1

.........At 0530 hours, B Company led 2 Devon’s advance westward from Ryes to the Masse de Cradalle, which was occupied without opposition at 0700 hours. C Company rejoined the battalion from its overnight location in la Rosiere and took the lead towards the village of Longues with Lieutenant Colonel Nevill’s Tactical HQ and the remainder of the battalion following. The commanding officer recorded that:

“When we got to within 3,000 yards of the village we had our first view of the battery itself Lieutenant Frank Pease, now commanding C Company, and I, looking through our field glasses, wondered whether in fact it was occupied. Our doubts were soon dispelled by the appearance of two Germans walking slowly across the area. At this moment, the Brigade Commander arrived to say that HMS Ajax and a squadron of fighter-bomber’s would be available to support the attack. As we knew the strength of the position was still formidable, in spite of the RAF softening up, we gladly made use of their assistance. It was decided that Ajax would fire from 0815 until 0845 hours, at which time the squadron of fighter-bombers would blast the place for five minutes. The MG Platoon of 2 Cheshire, under Capt Bill Williams, would give direct support to the infantry attack, timed to take place at 0900 hours.â€

C Company was to deliver the attack. Lieutenant David Holdsworth recalled that the bombardment was “a marvellous spectacle, and we wondered how anybody could still be alive in the great concrete-faced batteryâ€. The plan was to attack through the village, astride the road, where the minefields appeared to be fewer. Lieutenant Holdsworth described C Company’s advance, which began at 0852 hours, “accompanied by a party of Brigade and Divisional staff officers who had come along for the fun of itâ€:

“This was a set piece battle and, apparently, a lot depended upon it. The two leading platoons and the acting company commander (Lieutenant Pease) made their tortuous way towards the battery. There was no sound from it, either because the enemy were holding their fire or because they were dead.â€

There is no mention in any accounts of casualties from mines during the attack. Presumably, a high proportion of the minefields were dummies and the Royal Navy and RAF bombardment had sympathetically detonated many others. It is highly likely that, with landmines not being a normal Kriegsmarine inventory item, the number laid was limited. Lieutenant Holdsworth continued:

“In the rear came my platoon. To my surprise, the two leading platoons made their way beyond the place from which they were expected to carry out the final assault. My platoon was just about level with it. The acting Company Commander realized this. Time was against a complete reorganization to carry out the original assault plan by 0900 hours. There was only one thing to do. And he did it. He ordered an about turn. The effect was to make my platoon into the lead platoon and, therefore, commit it to immediate attack. Faced with barbed wire encircling the whole of the approach to the battery, and with those wretched “Achtung Minen!†signs generously scattered round the area, we felt pitifully inadequate to the demands of the situation. The only pleasant feature about the whole affair was the fact that no-one was firing at us from the battery. We advanced to the wire in a very open formation. Still there was no sound from the enemy. Gingerly we stepped over the wire and down one of the criss-cross paths. At that moment one of the massive iron doors of the battery swung open. Out came the enemy with white flags held out in front of them.â€

However, not all of the Kriegsmarine gunners were prepared to surrender so easily and machine-gun and rifle fire was directed at the Devon’s from across the battery. This complicated and slowed down the clearance of the positions, which was a labyrinth of bunkers, blown-in trenches and a few tunnels. With some enemy still active, the Devon’s had to assume the worst and methodically clear the battery. In doing so, they suffered a number of casualties, including Captain Nobby Clark, who was killed near the German command post on the cliff edge, which held out longer than other parts of the battery. Private Kerslake recalled:

“We attacked one of the gun bunkers, where we had to go round to the front as we couldn’t make any impression on the heavy door at the back. As we went around the mounds of earth, we came under fire from a very heavy calibre machine gun, probably one of the 20mm guns, and only survived as there were plenty of craters from near-misses to hide in. After my experience of the landing the day before, I was not looking forward to clearing the gun bunker and, even though it was hot, I was in a cold sweat. Under covering fire we went in. After the bright daylight, we couldn’t see anything. There were shots that dangerously ricocheted off the walls. I never did find out if they were ours or theirs. We went through the bunker; we had been warned not to use grenades, as we would have in normal buildings, as we could have exploded ammunitions and ourselves with it. We reached the back door and opened it and I nearly got shot by a very young lad from our platoon who was on his own; very jumpy and very white.â€

At 1053, the battery was reported as captured; in addition to the naval guns, a 76mm field gun was captured, along with its crew, dug-in within the perimeter. Following the German surrender and the taking of ninety prisoners, out of a reported strength of 184 Kriegsmarine gunners, Lieutenant Holdsworth explained:

“Tension eased immediately. The enemy walked down one of the paths towards us. We walked up the same path towards them. The battery was ours. Over a hundred enemy soldiers came out of the concrete-covered chambers inside the battery, all with their hands up. Inside the chamber was a smell, which I can only describe as the smell of human fear. Having witnessed the bombardment to which they had been subjected, it wasn’t really surprising that they had surrendered. I would have done the same.â€

A Devon recalls a chance meeting at the battery with one of the German prisoners many years later:

“The German told us he was a sailor not a soldier but he had never been to sea. This we had not known and I began to feel for him when he explained how the RAF had hit his battery regularly and how they felt like sitting ducks on the cliff top. The sight of the invasion fleet was intimidating and it was only our Navy’s gunfire that prevented many of them from running away! They had no instruction what to do but the officers said that they were to fight us “Tommies†when we came but the final bombardment convinced several groups to surrender.â€

Overall, the Longues-sur-Mer Battery, arguably a formidable fortification, did not prove to be as dangerous as was thought. The weight of well coordinated Allied firepower was brought to bear and effectively neutralized the enemy guns and gunners. So shocked were the Germans that 2 Devon’s ‘attack’ was more a mopping-up operation than a true attack.

Lieutenant Holdsworth described the aftermath of the attack:

“Having disposed of the battery successfully and, to their relief without much trouble, my platoon displayed many of the usual symptoms of a victorious army. Inside the fortified central chamber were pictures of Hitler and other German leaders. Possibly because we hadn’t had to shoot anyone in anger, mixed feelings of relief and achievement found expression in the destruction of all the pictures hanging on the walls. Fortunately, this mood of destruction didn’t last long, and within a few minutes we collected ourselves together and formed again into a fairly recognisable, disciplined unit. Some pockets bulged with loot but, on the whole, we had behaved as well as any soldier can be expected to behave on these occasions. It had been exciting and, thank goodness, an entirely successful military operation for us, and we now indulged in noisy high spirits. Back we went to our company transport.â€

Overall, the Longues-sur-Mer Battery, arguably a formidable fortification, did not prove to be as dangerous as was thought. The weight of well coordinated Allied firepower was brought to bear and effectively neutralized the enemy guns and gunners. So shocked were the Germans that 2 Devon’s ‘attack’ was more a mopping-up operation than a true attack.

(From a post by “Jim†on the War44.com forum)

The first gun was severly damagaed. Not by gun or bombs but the RAF at the nearby airfield stored munitions in here and an accident blew it up.

Here you can see the damage done to the bunker on the upper right hand side.

Must've been quite the explosion.

Remains of the gun:

Moving down the path to Gun#2:

Gun#2, The holes in the top of the bunker were not caused by bombs or shells but were intentionally put there so as to be able to attach netting and camoflage.

Gary (our guide) explaining the workings of the gun inside Bunker# 2

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

I see some of the pictures have issues.

I'll fix those at a later date...

I hope you enjoy the tour

Day 5 - Various

Longues-sur-Mer - Gun battery original coastal guns

Cristot - Sunken lane CSM Stan Hollis VC action against 12SS

Audrieu - Chateau - HQ 12SS Reconnaissance Battalion - Scene of executions

Audrieu - Monument to the murdered

Putot-en-Bessin - Monument in the village to the Canadian units - Royal Winnipeg Rifles and Canadian Scottish

Bretteville L'Orgueilleuse - Regina Rifles/12th SS Panzer Division/knocked out Panther tank and destroyed church

Rots - 46 Commando Memorial

Rots - Canadian Scottish/Chaudiere/Fort Garry Horse Memorial & Passage Leon Gagne (married the bakers

daughter)

Rots - Church square - tank battles with 12th SS

Abbey d'Ardennes - 12th SS Panzer/25th Panzer Grenadiers Regimental HQ - Kurt Meyer - Canadian prisoners

executed 7th (plus other dates) June 1944.

Lunch at Bretteville-sur-Odon

Hill 112 - 43rd Wessex Division v various SS units 1/9/10 and 12

Villers Bocage

Tilly-sur-Seulles - British Cemetery

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(Note-This will be the longest post of Day 5 because there were so many good photo opportunities.)

First thing we did on Day 5 of the tour is head over to the gun battery at Longues-sur-Mer.

This, I would guess, is the best preserved battery in all of Normandy.

But first, right next to the Longues-sur-Mer Battery is a memorial who commerates the Allied airfield (B11) which was in service between 21 June and 4 September 1944. The airfield was located 300 metres east of the battery.

Longues-sur-Mer airfield (Advanced Landing Ground B-11 Longues-sur-Mer) was an airfield on the Normandy beachhead in France, 7 kilometers north of Bayeux.

The airfield became operational on 26 June 1944.

To cover the runway, the British set up anti-aircraft guns on the roof of the Longues-sur-Mer coastal artillery bunker .

Inside the former German bunker they stored the ammunition for the airfield.

An explosion in this makeshift magazine caused the deaths of four soldiers.

The violence of this explosion was so great it led to the total destruction of a blockhouse built by the Germans and a twisted gun barrel in front of the casemate.

The airfield was used by the Royal Air Forces 125 Wing (132 Sqn (RAF), 602Sqn (RAF), 453 Sqn (RAAF), 441Sqn (RCAF).

During their operations from Longues-sur-Mer, both 602Sqn and 453Sqn claimed to have strafed a German staff car.

(The same claim was also made by 412Sqn RCAF)

The attack severely injured Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, who fractured his skull.

Generalfeldmarschall Rommel had to be hospitalised for weeks, keeping him from the battlefield.

This was an area without much bocage and ideal for airfields.

Monument to the fliers of airfield B11

A Spitfire of the Royla Air Force under the protection of apple trees on the airfield ALG B-11 Longues

A picture taken here of the Wing Commander, AG Page, leader of the No. 125 Wing , in the cockpit of a Supermarine Spitfire.

From here we drove over to the battery and started our walk down the path that circles the battery.

The Longues-sur-Mer battery was a World War II artillery battery constructed by the Wehrmacht near the French village of Longues-sur-Mer in Normandy. It formed a part of Germany's Atlantic Wall coastal fortifications.

The battery was completed by April 1944. Although constructed and manned initially by the Kriegsmarine, the battery was later transferred to the German army. The site consisted of four 152-mm navy guns, each protected by a large concrete casemate, a command post, shelters for personnel and ammunition, and several defensive machine-gun emplacements.

The battery at Longues was situated between the landing beaches Omaha and Gold. On the night before the D-Day landings of 6 June 1944, the battery was subjected to a barrage comprising approximately 1,500 tons of bombs, although much of this landed on a nearby village. The bombing was followed from 0537hrs on the morning of the landings by bombardment from the French cruiser Georges Leygues as well as the U.S. battleship Arkansas. The battery itself opened fire at 0605hrs and fired a total of 170 shots throughout the day, forcing the headquarters ship HMS Bulolo to retreat to safer water. Three of the four guns were eventually disabled by British cruisers Ajax and Argonaut, though a single gun continued to operate intermittently until 1900hrs that evening. The crew of the battery (184 men, half of them over 40 years old) surrendered to the 231st Infantry Brigade the following day.

The heaviest damage was caused by the explosion of the ammunition for an AA gun, mounted by the British on the roof of casemate No.4, which killed several British soldiers.

At 05:30 hrs on D-Day, the batterie was engaged by the French cruiser, FFS Georges Leygues and the American battleship USS Arkansas.The batterie opened fire on the destroyer Emmons stationed off Omaha beach. Due to the fact that the underground cables from the Fire control bunker had been destroyed by the previous bombing raids, the gunners used their direct sights to engage the invasion fleet.

The batterie then engaged the Arkansas..The French cruiser Montcalm also became involved in the exchange of fire.

30 minutes later, the guns then turned their attention to Gold sector and engaged HMS Bulolo, the Gold flagship with the Army Corps commander on board.The accuracy of the batterie forced the ship to weigh anchor. After a further 20 minutes of bombardment, it fell silent.

Ajax was joined by HMS Argonaut in shelling the batterie which was put out of action at 08:45hrs.It had taken 179, 6" and 5.25" shells from the two cruisers. Two of the casemates received direct hits through their embrasures....

The French and the British both claimed the defeat of the batterie as their own....

The two remaining guns opened up again in the late afternoon but were silenced by the French cruiser, FFS Georges Leygues The batterie's 120 survivors out of 184 crew , surrendered the next day to the British 231st Infantry Brigade. The batterie had fired a total of 115 rounds.

(From the Cool Blue Blog)

Here you can get a sense of the results of sea and air bombardment on the battery.

The obeservation bunker is on the left at the edge of the cliff. Two of the batteries are circled.

A closer view:

D-Day Action

There is a degree of controversy between the British and French over the naval engagement of Longues-sur-Mer. However, naval logs of the ships concerned provide a precise record of the action.

At 0500 hours, HMS Ajax was lying at anchor six nautical miles to the north of Longues-sur-Mer. Captain Weld, searching the coastline through his binoculars in the early dawn light, saw the low silhouette of the battery on the cliff top. At 0530 hours (sunrise minus forty minutes) he ordered his eight 6-inch guns to open fire. At first, there was no response. However, the battery opened fire, initially at the destroyer USS Emmons at 0537 hours, but switched its fire to the battleship USS Arkansas lying off Omaha at a range of ten miles.

Arkansas and the French cruiser Georges Leygues joined Ajax’s engagement, firing twenty twelve-inch and one hundred and ten five-inch shells, and the battery fell silent. At 0557, the battery again opened fire, this time to the east, at the anchored HMS Bulolo off Gold, with the first rounds from Number 3 and 4 guns straddling the target.

Bulolo was a prime target, being the Naval Force G’s flagship and 50th Division’s HQ ship and, therefore, a vital nerve centre. She quickly weighed anchor and moved seaward. At 0605 hours Number 1 and 2 guns re-engaged Arkansas and the two French cruisers. In response, FFS Montcalm joined HMS Ajax in her redoubled rate of fire and, by 0620 hours, the battery was again silenced. Over the next two hours, the battery came into action again several times, engaging targets in the Gold area. HMS Argonaut joined Ajax and fired twenty-nine and one hundred and fifty rounds respectively before the battery was silenced at 0845 hours. The guns in casemates 3 and 4 were knocked out, while numbers 1 and 2 were damaged.

By late afternoon, the Kriegsmarine gunners had repaired Number 1 gun, which, because the open front was facing slightly to the west, had been more difficult for Ajax to engage effectively. This gun opened fire on shipping off Omaha, where the battle was only just swinging in the Americans favour.

George Leygues, under command of Naval Bombardment Force C, replied. There was a terse exchange of Aldis Lamp signals between Captain Weld and Admiral Jaujard, the former claiming the battery as Ajax’s exclusive target. The French were not impressed and George Leygues continued to engage! Number 1 gun was finally put out of action at 1800 hours, by the fire of both ships. From the number of empty cylinders in the casemates, it is estimated that the battery fired approximately one hundred and fifty rounds during the course of D-Day. Without the air and naval bombardment, the effect of these shells, and 1,050 rounds found in the battery’s magazines, would have been highly significant, especially off Omaha, where the battle hung in the balance for most of the day.

Commander Edwards attributes Longues-sur-Mer’s neutralisation to some exhibition shooting on the part of Ajax, which will long be quoted as an instance of amazing gunnery by a ship against a shore battery. 2 Devon’s ground attack planned for D-Day did not take place as scheduled. The delay on the beach and more determined resistance than expected caused the battalion to halt at Ryes for the night.

HMS Ajax on D-Day against Longues-sur-Mer Battery.

The Attack on D+1

.........At 0530 hours, B Company led 2 Devon’s advance westward from Ryes to the Masse de Cradalle, which was occupied without opposition at 0700 hours. C Company rejoined the battalion from its overnight location in la Rosiere and took the lead towards the village of Longues with Lieutenant Colonel Nevill’s Tactical HQ and the remainder of the battalion following. The commanding officer recorded that:

“When we got to within 3,000 yards of the village we had our first view of the battery itself Lieutenant Frank Pease, now commanding C Company, and I, looking through our field glasses, wondered whether in fact it was occupied. Our doubts were soon dispelled by the appearance of two Germans walking slowly across the area. At this moment, the Brigade Commander arrived to say that HMS Ajax and a squadron of fighter-bomber’s would be available to support the attack. As we knew the strength of the position was still formidable, in spite of the RAF softening up, we gladly made use of their assistance. It was decided that Ajax would fire from 0815 until 0845 hours, at which time the squadron of fighter-bombers would blast the place for five minutes. The MG Platoon of 2 Cheshire, under Capt Bill Williams, would give direct support to the infantry attack, timed to take place at 0900 hours.â€

C Company was to deliver the attack. Lieutenant David Holdsworth recalled that the bombardment was “a marvellous spectacle, and we wondered how anybody could still be alive in the great concrete-faced batteryâ€. The plan was to attack through the village, astride the road, where the minefields appeared to be fewer. Lieutenant Holdsworth described C Company’s advance, which began at 0852 hours, “accompanied by a party of Brigade and Divisional staff officers who had come along for the fun of itâ€:

“This was a set piece battle and, apparently, a lot depended upon it. The two leading platoons and the acting company commander (Lieutenant Pease) made their tortuous way towards the battery. There was no sound from it, either because the enemy were holding their fire or because they were dead.â€

There is no mention in any accounts of casualties from mines during the attack. Presumably, a high proportion of the minefields were dummies and the Royal Navy and RAF bombardment had sympathetically detonated many others. It is highly likely that, with landmines not being a normal Kriegsmarine inventory item, the number laid was limited. Lieutenant Holdsworth continued:

“In the rear came my platoon. To my surprise, the two leading platoons made their way beyond the place from which they were expected to carry out the final assault. My platoon was just about level with it. The acting Company Commander realized this. Time was against a complete reorganization to carry out the original assault plan by 0900 hours. There was only one thing to do. And he did it. He ordered an about turn. The effect was to make my platoon into the lead platoon and, therefore, commit it to immediate attack. Faced with barbed wire encircling the whole of the approach to the battery, and with those wretched “Achtung Minen!†signs generously scattered round the area, we felt pitifully inadequate to the demands of the situation. The only pleasant feature about the whole affair was the fact that no-one was firing at us from the battery. We advanced to the wire in a very open formation. Still there was no sound from the enemy. Gingerly we stepped over the wire and down one of the criss-cross paths. At that moment one of the massive iron doors of the battery swung open. Out came the enemy with white flags held out in front of them.â€

However, not all of the Kriegsmarine gunners were prepared to surrender so easily and machine-gun and rifle fire was directed at the Devon’s from across the battery. This complicated and slowed down the clearance of the positions, which was a labyrinth of bunkers, blown-in trenches and a few tunnels. With some enemy still active, the Devon’s had to assume the worst and methodically clear the battery. In doing so, they suffered a number of casualties, including Captain Nobby Clark, who was killed near the German command post on the cliff edge, which held out longer than other parts of the battery. Private Kerslake recalled:

“We attacked one of the gun bunkers, where we had to go round to the front as we couldn’t make any impression on the heavy door at the back. As we went around the mounds of earth, we came under fire from a very heavy calibre machine gun, probably one of the 20mm guns, and only survived as there were plenty of craters from near-misses to hide in. After my experience of the landing the day before, I was not looking forward to clearing the gun bunker and, even though it was hot, I was in a cold sweat. Under covering fire we went in. After the bright daylight, we couldn’t see anything. There were shots that dangerously ricocheted off the walls. I never did find out if they were ours or theirs. We went through the bunker; we had been warned not to use grenades, as we would have in normal buildings, as we could have exploded ammunitions and ourselves with it. We reached the back door and opened it and I nearly got shot by a very young lad from our platoon who was on his own; very jumpy and very white.â€

At 1053, the battery was reported as captured; in addition to the naval guns, a 76mm field gun was captured, along with its crew, dug-in within the perimeter. Following the German surrender and the taking of ninety prisoners, out of a reported strength of 184 Kriegsmarine gunners, Lieutenant Holdsworth explained:

“Tension eased immediately. The enemy walked down one of the paths towards us. We walked up the same path towards them. The battery was ours. Over a hundred enemy soldiers came out of the concrete-covered chambers inside the battery, all with their hands up. Inside the chamber was a smell, which I can only describe as the smell of human fear. Having witnessed the bombardment to which they had been subjected, it wasn’t really surprising that they had surrendered. I would have done the same.â€

A Devon recalls a chance meeting at the battery with one of the German prisoners many years later:

“The German told us he was a sailor not a soldier but he had never been to sea. This we had not known and I began to feel for him when he explained how the RAF had hit his battery regularly and how they felt like sitting ducks on the cliff top. The sight of the invasion fleet was intimidating and it was only our Navy’s gunfire that prevented many of them from running away! They had no instruction what to do but the officers said that they were to fight us “Tommies†when we came but the final bombardment convinced several groups to surrender.â€

Overall, the Longues-sur-Mer Battery, arguably a formidable fortification, did not prove to be as dangerous as was thought. The weight of well coordinated Allied firepower was brought to bear and effectively neutralized the enemy guns and gunners. So shocked were the Germans that 2 Devon’s ‘attack’ was more a mopping-up operation than a true attack.

Lieutenant Holdsworth described the aftermath of the attack:

“Having disposed of the battery successfully and, to their relief without much trouble, my platoon displayed many of the usual symptoms of a victorious army. Inside the fortified central chamber were pictures of Hitler and other German leaders. Possibly because we hadn’t had to shoot anyone in anger, mixed feelings of relief and achievement found expression in the destruction of all the pictures hanging on the walls. Fortunately, this mood of destruction didn’t last long, and within a few minutes we collected ourselves together and formed again into a fairly recognisable, disciplined unit. Some pockets bulged with loot but, on the whole, we had behaved as well as any soldier can be expected to behave on these occasions. It had been exciting and, thank goodness, an entirely successful military operation for us, and we now indulged in noisy high spirits. Back we went to our company transport.â€

Overall, the Longues-sur-Mer Battery, arguably a formidable fortification, did not prove to be as dangerous as was thought. The weight of well coordinated Allied firepower was brought to bear and effectively neutralized the enemy guns and gunners. So shocked were the Germans that 2 Devon’s ‘attack’ was more a mopping-up operation than a true attack.

(From a post by “Jim†on the War44.com forum)

The first gun was severly damagaed. Not by gun or bombs but the RAF at the nearby airfield stored munitions in here and an accident blew it up.

Here you can see the damage done to the bunker on the upper right hand side.

Must've been quite the explosion.

Remains of the gun:

Moving down the path to Gun#2:

Gun#2, The holes in the top of the bunker were not caused by bombs or shells but were intentionally put there so as to be able to attach netting and camoflage.

Gary (our guide) explaining the workings of the gun inside Bunker# 2

Last edited: